Turning the tide on place-based health inequalities

Luke Munford, Senior Lecturer in Health Economics, University of Manchester

The threads of power and place run through everything we are exploring in UK 2040 Options. Understanding how power and place interact, and how they impact people and communities, is critical to understanding how we might make the UK a fairer place to live. This is part of a series of guest essays that explores these themes.

England is a deeply unequal country. Health, wealth, and opportunities to thrive differ greatly depending on where we live and work.

The relationship between health and place can be considered in terms of the interplay between who lives in a place, what the place is like and the wider public policy context. Often, individual circumstances interact with the place where people live to exacerbate or reinforce inequalities in health outcomes.

In this piece, I highlight the worrying statistics that show the level of health inequality in England and why policymakers must consider a hyperlocal approach. I also outline the policy options that local and central government have available to help tackle place-based health inequalities.

The UK has wide place-based health inequalities: and they are growing

The UK ranks among the highest in terms of regional economic inequalities among OECD countries. The north of England bears the brunt of these inequalities, with lower economic productivity as well as lower life expectancy than the south of England. Nationally, coastal communities grapple with a higher burden of ill-health and substance misuse.

Our analysis of the most recent data shows that on average, males living in the most deprived areas of England are expected to live 9.7 fewer years than males in the least deprived areas. Females living in the most deprived areas can expect to live 8 fewer years than females in the least deprived areas.

These gaps are even bigger when we consider healthy life expectancy, an estimate of lifetime spent in very good or good health. Males living in the most deprived areas have a healthy life expectancy that is 18.2 years lower than males living in the least deprived areas. Females living in the most deprived areas have a healthy life expectancy that is 18.8 years lower than females living in the least deprived areas.

Worryingly, there is a downward trend in life expectancy for those living in the most deprived areas meaning that the gaps between the most deprived and least deprived areas have been growing over time.

“Despair” is not uniformly spread throughout England

In 2015, a phenomenon coined ‘deaths of despair’ emerged in the US, highlighting an increase in deaths caused by drug and alcohol misuse as well as suicide. The underlying cause of these deaths in the US is long-term economic disadvantage: low levels of education, income inequality and poverty, as well as a breakdown of community and social structures, including insecure and low-paid jobs, income inequality, housing evictions and workplace automation.

In a study that my team at the University of Manchester recently conducted, we used the latest available data from England to see whether there was a similar trend. It showed us that between 2019-21, 46,200 lives were lost to deaths of despair (equivalent to 42 each day) with an average rate for England of 34 lives lost per 100,000 people.

But below this average hid significant regional disparities, mapping on to what we know about place-based inequality. The North East had the highest burden, averaging 55 deaths of despair per 100,000 people, but in stark contrast, London’s rate was very low, with around 25 per 100,000. Despair therefore seems to not be uniformly spread throughout England: of the 20 local authorities with the highest rates of deaths of despair, 16 were in the north – but none of the 20 areas with the lowest rates were. These are stark and unacceptable differences.

To understand what might be driving these gaps, we identified a number of area-level factors that were associated with the elevated risk of deaths of despair. These included high unemployment rates, higher proportions of White British ethnicity, solitary living, higher rates of economic inactivity, employment in elementary occupations, and whether the community was urban (compared to rural). This also emphasised that deaths of despair are not inevitable – but rather a tragic consequence of inequitable resource distribution.

Deprivation interacts with place, amplifying its impact

While deprivation and the lack of resources available to people and places are key drivers of health inequalities, there is evidence that region-level deprivation interacts with and amplifies the effect of small area deprivation. We can see deeper health inequalities at a hyperlocal level: this is a phenomenon that we have called ‘deprivation amplification’.

We see this throughout England. Persistent inequalities, evolving over recent decades, have led to the creation of ‘left-behind’ communities. While the use of the phrase left-behind has generated some controversy, it reflects that a set of neighbourhoods and communities have higher levels of need and have largely been forgotten by national policy. There are 225 left-behind neighbourhoods, which are mostly found in post-industrial areas in the north of England and the Midlands.

Again, this has an impact on health outcomes: in left-behind neighbourhoods, men live 3.7 years fewer than average and women 3 years fewer. Both men and women in these neighbourhoods can expect to live 7.5 fewer years in good health than their counterparts in the rest of England, and there is a higher prevalence of 15 of the most common health conditions, even when compared to other deprived areas. This has an economic impact: individuals are twice as likely to claim incapacity benefits due to mental health-related conditions when compared to England as a whole.

This deprivation amplification was particularly acute during the Covid-19 pandemic. Across England, the most deprived areas had the highest rates of Covid-19. But when deprived areas in the north were compared to areas that were equally deprived in other parts of England, we found that northern areas had significantly higher rates of mortality. We found that deprivation alone could not explain these very stark differences. And again, people living in left-behind neighbourhoods in the early stages of the pandemic were 46% more likely to die from Covid-19 than from those in the rest of England.

Options for a more equal England

Interpreting the complex interrelationships between health and place relies heavily on the availability of high-quality data and the definition ‘place’. However, the way that we currently measure the health of a place is based on geographic definitions that are not always meaningful when it comes to supporting decision-making about how to improve health.

For example, Liverpool has the fifth-lowest life expectancy for males if we consider local authority averages. Yet of the 62 middle super output areas (MSOAs) that make up Liverpool, 10 of them have above the national average male life expectancy. Conversely, not all MSOAs within the local authorities that have the best health outcomes experience the best health. For example, based on census data, 12% of areas within Richmond on Thames (the local authority with the highest life expectancy) reported below average levels of very good or good health.

Therefore, if we base funding decisions solely on local authority averages, we mask really important variation that tells us about the health of communities and where services might be needed.

We need to tackle the hyperlocal differences in health outcomes, as well as the between regions and between local authority differences. But the way policymakers currently think about place-based health inequalities is insufficient, as decisions are based on their understanding on averages of disparate areas. And the way that most people conceptualise ‘place’ is very often different to how geographical boundaries are drawn. For example, most people have no idea which MSOA they live in: instead, we tend to define where we live through key landmarks.

We can see this insufficient consideration of place play out in the previous UK Government’s Levelling Up agenda. Our research has previously raised concerns around whether funding is allocated equitably. Around £125 million was allocated to England in the first round of the Community Renewal Fund (one of the first flagship ‘levelling up’ funding pots). However, when a ‘fair share’ funding allocation was created (based on the UK Government’s own formula) and compared to the actual allocation of funding, large place-based inequalities emerged. The North East received £13.4 million less than expected based on its resilience score. At the other end of the scale, the South East received £3 million more from than expected. Overall, analysis showed no significant correlation between need and actual Community Renewal Fund allocations.

The implication of our work is therefore clear: preventive policies must be geographically tailored. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to fixing regional inequalities, and knowing where the hotspots of poor health really are will mean that policymakers can target funding in a much more nuanced way.

We have set out a series of policy options below. Devolving greater decision-making powers and funding to local and regional governments offers one avenue for delivering bespoke solutions. Greater powers are needed for Metro Mayors to direct financial, health, and community resources towards the areas hit hardest by unfair health inequalities. This is underway in Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, with their ‘trailblazer deal’, but this new data highlights the urgent need to accelerate the devolution of place-based powers.

However, the national policy context – prioritising equitable access to economic opportunities, the labour market, and housing – remains paramount in reducing health inequalities by tackling the social determinants of health. This has been shown to be successful in the past in the UK at reducing inequalities in life expectancy, infant mortality and mortality at age 65. Tackling these socio-economic factors requires interdepartmental collaboration, cross-party working and a long-term commitment to levelling up. The responsibility falls across Government to ensure health is embedded in all decisions aimed at reducing inequalities.

Options

What Westminster can do

- A national strategy developed to reduce health inequalities through targeting multiple neighbourhood, community and healthcare factors. However, this needs to be allocated based on need, so that more deprived and left-behind communities receive their fair share.

- The impact on health, and health inequalities, should be taken into account when making all government decisions, regardless of which government department is making the policy.

- An increase in NHS funding in more deprived local areas (including left behind neighbourhoods) to reduce healthcare inequalities.

- Long-term ring-fenced funding put in place for targeted health inequalities programmes, and focussed at the hyper-local neighbourhood level.

What mayoral/combined authorities and local authorities can do

- Local governments should have increased freedom over their spending to ensure it is used in the best way to tackle health inequalities. In particular, following on from the Health Foundation work, local authorities should utilise hyperlocal data to identify the areas with the highest burdens of disease and use this to target services within their jurisdiction.

- Consistent and long-term financial support should be ring-fenced for communities to engage in neighbourhood-based health initiatives. For example, a Community Wealth Fund, which, if implemented, could offer a means of improving social infrastructure and empowering communities by placing neighbourhoods at the heart of decision-making.

- Programmes developed to increase community engagement to better understand and identify the issues and barriers faced by individuals, and thereby improve the quality of local services.

- Set up community consultation processes in left-behind neighbourhoods to identify the issues facing local communities.

What local government and communities can do

- Fund health initiatives that increase the level of control local people have over their life circumstances, such as the community piggy bank.

- Put community engagement which builds social cohesion, networks and infrastructure at the heart of health delivery.

- Help communities to take ownership of community assets facilitated by sufficient help and support from national and local government.

- Support and incentivise residents to make the most of community assets and maintain their participation through schemes such as lower transport costs.

- Existing services should be redesigned to respond to specific challenges within an area.

If we get this right, there is much to be gained. Not only will it improve the lives of millions of people living throughout England, it will also bring significant savings to the taxpayer. If the health outcomes in local authorities that contain left behind neighbourhoods were brought up to the same level as in the rest of the country, an extra £29.8 billion every year could be put into the country’s economy.

Fixing health inequalities must be a moral urgency for this new UK Government.

Dr Luke Munford is a Senior Lecturer in Health Economics at the University of Manchester and deputy theme lead for Economic Sustainability within the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration in Greater Manchester (ARC GM). He is a quantitative researcher who uses existing data to understand the causes and consequences of health inequalities, with a strong emphasis on place, including focussing on the interactions between people and place. He is also academic co-director of Health Equity North. Health Equity North is a virtual institute focused on place-based solutions to public health problems and health inequalities, bringing together world-leading academic expertise from leading universities and hospitals across the North of England.

Navigating policy complexity: a Delphi method approach

By Ben Szreter, Rachel Carter and Esme Yates

The Oracle of Delphi in Ancient Greece was considered a powerful source of prophecy and insight. Being able to predict the future would, of course, be the ultimate tool for policymaking. But while this is impossible, using a technique named after this ancient oracle – the Delphi method – could be an underutilised asset in policy development.

A Delphi approach can help identify people’s ideas about the future and calibrate those ideas against each other. The unique selling point of the Delphi method is that group decisions and analysis – without the biases that come with group hierarchies – can be better than an individual’s alone. This is as true in policy as in other areas and could be especially pertinent in complex policy landscapes where traditional approaches may fall short.

There have been examples of the Delphi method being used in policymaking from the 1970s, but its use has not been widespread. For example, it has previously been used in forecasting (on topics such as public policy issues, economic trends, health and education), and to help reach expert consensus in health-related settings, such as in the development of medical guidelines and protocols.

In the UK 2040 Options project, we have set out to draw on collective wisdom as we consider policy options that will get the UK to a better place by 2040. In some instances, we have used an adapted Delphi process to draw on a wide range of expert perspectives, which has given us a large funnel through which to filter the wide range of issues and ideas that we are exploring.

What is a Delphi exercise and how have we run them?

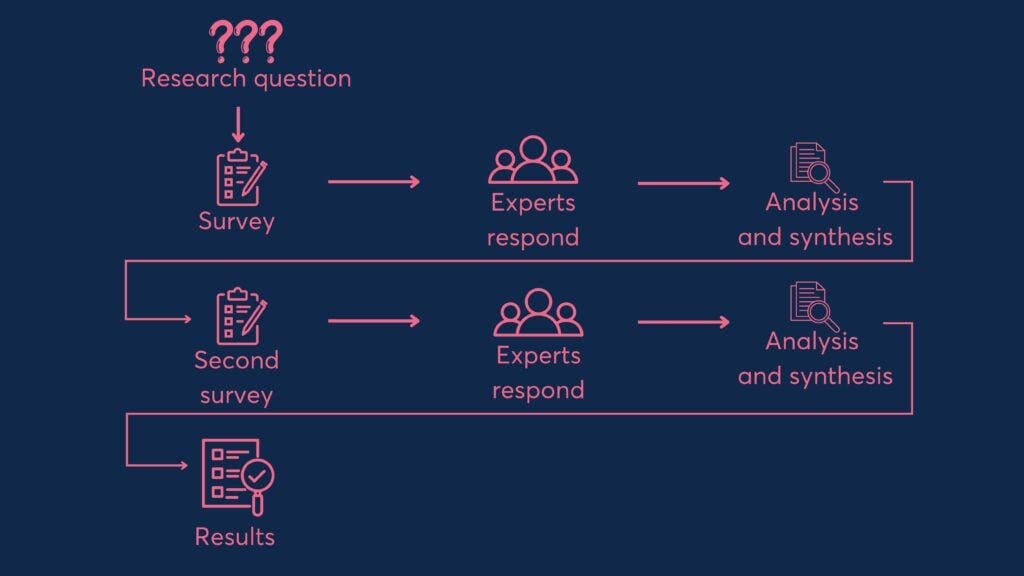

Our Delphi exercises included two rounds. In round one, we asked respondents about the issues and interventions that could impact the topic in question in the UK (such as economic growth) and to rank their responses by importance or potential impact. In round two, we fed these issues and interventions back to the respondents alongside their average importance or impact scores from round one, before asking the experts surveyed for their final judgement. Opinions of all experts were kept anonymous throughout.

The final output is a list of policy issues and interventions, ranked by the scores given by experts in round two.

This process can be seen in the below diagram.

How we’ve used the Delphi method to crowdsource expert views

We have run Delphi exercises on policy topics such as growth and productivity, education, health and net zero. In our adaptation of the Delphi method, we aimed to capture the multifaceted nature of policy issues surrounding various major policy problems in the UK.

Across these Delphis, we have been able to engage with a diverse group of more than 250 experts in total, identify well over 100 critical issues and propose over 900 potential interventions. Using this method has allowed us to get much richer information from experts and emerging thinkers, in a more useable way, than a traditional survey or roundtable alone.

What we gained from using Delphis in a policy context

The Delphi process is a good way to cast a wide net for different views and perspectives on a particular topic. It allowed us to quickly identify the most important issues that there is expert consensus around, as well as pinpoint a wide set of possible interventions.

This helped us to focus subsequent in-person discussions on policy priorities around areas that had been identified as being of the most concern and gave us an understanding of where there is convergence in opinion (the “no brainers”) and where there is divergence (a potential choice for policymakers to make). The suggested interventions also acted as a spark for discussions with experts around trade-offs, the feasibility of implementation, and where government attention should focus next.

All of this provided rich and invaluable insight into specific policy areas, which we were able to draw on and distil in our public-facing research. You can see examples of how we used the outputs of the Delphi process in our education, health and wealth and income inequality ‘Choices’ series.

Insights we gained into the Delphi model

Participants were able to comment on the user experience of the Delphi, and provide feedback on the method and approach. From this, we were able to identify a number of key considerations.

- The wording of the questions needs to be succinct and well-considered. When working with people that have, at most, 10 minutes of focussed time, the research question has to be articulated quickly. Initially, the lack of specificity in some questions led to challenges in categorising responses for the second round of the Delphi, with some responses being very broad or vague (for example: income redistribution) and others being extremely specific (such as more effective limits on charging for school uniforms).

- Pre-specification is really important. Respondents sometimes mentioned the overwhelming nature of the survey’s second stage, citing the large number of items as a barrier to providing meaningful responses. It is therefore important to understand from the outset of the Delphi process what data will be categorised and how the results from the first phase will transfer to the second stage. This helps avoid bias in the approach and also helps formulate the questions.

- Be conscious of your sampling constraints. Given the nature of the task, there will sometimes be a low number of responses. And given the design of the survey, selection bias is likely to be present.

The feedback we received was instrumental in shaping our understanding of the Delphi process’s efficacy and limitations. It underscored the need for a delicate balance between comprehensive coverage of topics and the cognitive load on respondents.

We also learnt to categorise our issues, ensuring a clear distinction between causes, symptoms, and potential policy responses.

The Delphi method: a valuable policy tool

Despite its challenges, our experience with the Delphi method reaffirmed its value as a tool for policy analysis. It facilitated a structured yet flexible platform for gathering expert opinions, allowing us to quickly pinpoint areas of consensus and divergence. The method’s iterative nature, coupled with the anonymity of responses, also helped in reducing biases and promoting honest, uninhibited feedback.

Looking ahead, the Delphi method could hold significant promise as a versatile tool in the policymaker’s toolkit. Its application can be further refined to suit various policy domains, with modifications tailored to specific contexts and objectives.

Breaking the cycle: the outcomes model of public service?

Grace Duffy & Mila Lukic, Bridges Outcomes Partnerships

The threads of power and place run through everything we are exploring in UK 2040 Options. Understanding how power and place interact, and how they impact people and communities, is critical to understanding how we might make the UK a fairer place to live. This is part of a series of guest essays that explore how we might use new models of power and place to do just that.

Too many adults in the UK are stuck in a persistent cycle of unemployment, insecure housing and poor health. To break this invidious cycle, we need to think about public services – and invest in people’s skills – in a very different way.

Today, 4.3 million children in the UK live in poverty. In England alone more than 83,000 are looked after by the state, around 100,000 will leave school this year without qualifications and 20% are persistently absent from school. As a society we are facing intergenerational cycles of devastating outcomes cycles which can and must be broken to create a better society for the 2040 generation.

For the most part, the problem is not that the state is failing to reach the individuals behind these statistics. In fact, many of those in the most challenging circumstances have been through multiple public service interventions, at great cost and with good intentions, but without lasting success.

The problem is that we are not reaching the worst affected people early enough, and even when we do, the model for delivering services is fundamentally flawed.

A new paradigm for public services

In the UK, the traditional public services model is to standardise a particular process or intervention and deliver it in the same way, to anyone who needs it, as efficiently (and cheaply) as possible. This model focuses on immediate needs or problems to be fixed, and deals with them individually, in isolation – this is known as the ‘deficit model’.

This works very well for single issues with a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, such as mass vaccination or pension payments. However, it demonstrably fails to effectively address our society’s so-called ‘wicked problems’ – complex social problems without clear solutions, including multifaceted challenges such as family breakdown, long-term health conditions and homelessness.

This standardised deficit model has three key drawbacks. Firstly, by only focussing on ‘needs’ or ‘weaknesses’ (real or perceived) it can reinforce rather than break down the psychological barriers many people face when pursuing education and employment. Secondly, by focusing on isolated issues rather than trying to understand an individual’s situation more holistically, we often end up treating the symptoms rather than the underlying cause. And thirdly, it prohibits the personalisation needed to effectively address multifaceted challenges with complex interactions and instead takes a one-size-fits-all approach, treating everyone the same instead of treating them as individuals.

Fortunately, over the last decade, a new model of public services has started to emerge. This new paradigm recognises that what it takes to achieve positive outcomes is going to be different for everyone. It recognises that different places have different assets and priorities. It recognises that building on people’s strengths rather than focusing on weaknesses provides a better basis for sustained change. And it recognises that relationships are fundamental for thriving lives and communities.

At Bridges Outcomes Partnerships (BOP), we believe there are 12 essential ingredients when designing delivery to deal with these wicked problems.

Collaborative design

From programmes designed by a central department, often in isolation from other departments and implemented in a top-down way, to projects that:

- Bring community organisations together around a shared vision of success

- Co-create with real experts – frontline teams and participants themselves

- Join up with other local services via cross-government co-payment funds

- Operate as dynamic, actively managed partnerships by changing the nature of the contractual relationship between governments and delivery organisations.

Flexible delivery

From fixed-specification contracts that are delivered to rigid budgets for groups of people with identical needs to flexible, personalised services that:

- Tailor to peoples’ strengths by giving front-line teams the freedom to shape their services around individuals

- Invest properly in delivery teams by taking a more flexible approach to resourcing costs

- Embrace continuous improvement and allowing the service to be redesigned and ‘relaunched’ regularly

- Tackle systemic barriers to progress.

Clear accountability

From arms-length contracts with limited visibility on progress, success and key learnings to supportive partnerships which:

- Are transparent on progress by sharing regular updates against objective, clearly defined milestones

- Are accountable to those who access services

- Consider the longer-term impact of the service by finding light-touch ways to link into or compare with other government data

- Access and share learnings to benefit future services by investing in more sophisticated evaluations that tease out relative benefits of project features.

Since 2012, BOP has deployed these lessons through ‘outcomes partnerships’. These bring together multiple stakeholders to achieve meaningful change for people facing wicked problems, while helping create environments where delivery teams have more flexibility to personalise their delivery. By switching the focus to the desired goals rather than a specific delivery model, it allows for more personalised, localised programmes. The model also breaks down silos between systems to create more holistic – and therefore more effective – delivery of public services.

For example, in Kirklees, West Yorkshire, the local council recognised that its existing top-down, deficit-based model – using rigid service specifications focused on short-term needs – was consistently failing to achieve lasting change in people’s lives. So, together with the council, we created the Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership (KBOP). Its strengths-based, outcomes-focused approach to tackling persistent homelessness, drawing on community assets, has been much more successful.

Of the 6,379 people KBOP supported since September 2019, 73% of people have been able to keep their accommodation while 49% have entered education or employment compared to 43% of people sustaining accommodation and only 15% entering education or employment in the initial year. These outcomes demonstrate ongoing innovation in delivery and are outcomes with long-term impact:

- KBOP has reduced the need for repeat support by over 70%

- has been able to support more than twice as many people than predicted

- at an average cost-per-participant which is 39% lower to the commissioner than under the previous service.

Moving to a holistic, strengths-based approach to delivery through outcomes partnerships has not only transformed lives, it has resulted in much better value for taxpayers’ money.

Breaking the cycle: skills and education

This emerging model has important implications for our approach to skills and education – an essential foundation of fulfilling, stable lives. Our work supporting adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness demonstrates how this more personalised, strengths-based approach has helped practitioners approach skills in a different way and help people achieve sustained, positive changes in their lives.

Take the Greater Manchester Better Outcomes Partnership (GMBOP), a collaboration between mission-led organisations commissioned by Greater Manchester Combined Authority. This project supports young people at risk of homelessness. A lack of educational attainment was one of the biggest barriers to accessing stable employment and therefore housing. Many young people with highly transferable practical, creative and interpersonal skills are held back from jobs and apprenticeships because they don’t have a grade 4 GCSE in Maths or English.

By helping young people get qualified, GMBOP’s link workers have a huge impact, enabling them to access and sustain employment and accommodation. But first, they need to overcome the barriers that have stopped them in the past and lay the foundations for transformational change. This means taking a relational approach to improve resilience and confidence. And conceiving of skills in a wider sense to embrace essential soft skills such as communication, building relationships, setting goals and practical skills such as budgeting. Taking the time to develop foundational skills and focus on long-term outcomes helps these young people break their cycle of dependence on public services.

It follows then, that if we really want to tackle these problems we need to start early and prevent young people from getting trapped in these negative cycles in the first place.

That’s the key idea behind AllChild (formerly West London Zone), an outcomes-focused organisation that supports children and young people with an average of four risk factors across emotional, social and academic areas. None of these risk factors are, in isolation, bad enough to trigger statutory thresholds for children’s services. But taken together, they put the young person at high risk of negative outcomes, such as mental health challenges, being excluded from school, and/or falling into the ‘not in education, employment or training’ category.

AllChild’s two-year Impact Programme puts the child at the centre and personalises support around them, working with schools, early help, social care and local voluntary organisations to provide the tailored, holistic support they need. And it works. AllChild has supported more than 4,500 children across over 50 schools in West London. Three-quarters are no longer assessed as at risk in terms of their emotional and mental wellbeing, while two-thirds improved their grades.

A crucial factor in AllChild’s success is that it is deeply place-based. Extensive community co-design ensures interventions and services work in the local context, capitalising on local strengths. Indeed, building on its success in West London, this year AllChild has launched a new model in Wigan, Greater Manchester.

We need to change the system

These strengths-based, outcomes-focused programmes are hugely promising. But they remain the exception rather than the norm and there are systemic barriers to them realising their full potential. Most services designed to tackle ‘wicked’ problems are delivered with rigid service specifications that don’t allow for the personalisation possible under outcomes contracts – procurement processes and limited resources tend towards inflexibility, short-term budget cycles lead to short-term decisions and funding pressures result in prioritisation of crisis cases rather than prevention.

While this is understandable, it’s a false economy. Independent analysis (which has yet to be published) has found that outcomes partnerships such as AllChild deliver average total savings and wider economic benefits of £81,000 per child. This includes money saved by the state through the avoidance of negative outcomes, such as requiring child protection, and increased value from improved educational attainment and reduced exclusion. We must escape this ‘firefighting’ funding trap.

AllChild offers one potential solution. Partly because of its focus on place, it has been able to develop an innovative co-payment funding model. This brings together central and local government, local schools, local businesses and philanthropists to jointly pay for the positive outcomes the programme achieves, recognising that improving outcomes for children has benefits for the whole community. The model will soon be launched in Wigan – and can and should be replicated nationally.

Another crucial challenge is to target the right support, at the right time, to those most at risk of spiralling into negative outcomes.

In delivery, we see time and again the common factors trapping people in cycles of negative outcomes. And we see the enormous value of early intervention and prevention.

Where it’s been possible to securely link data sources, for example through Ways to Wellness, an asset-based social prescribing service, we have seen dramatic improvements in collective ability to understand what works and for whom leading to much improved outcomes for participants and cost savings to the NHS. With the advent of big data and AI, we have an opportunity to much more effectively target and tailor support for those who need it most.

The voluntary, community or social enterprise sector working on the frontline has a vital role to play in identifying those in need of help. Critically, the front line is the source of innovation and can also build the evidence base around how best to help people develop the skills they need to break negative cycles and improve their lives. We at Bridges Outcomes Partnerships would love to join forces with others who see the potential impact of truly holistic, place-based data and learning partnerships to get the right support to the right people at the right time. Given the likely state of the public finances over the next five years, improved targeting and investment in early intervention is clearly essential.

Solving these problems won’t be easy. Embracing this new approach to public services – more preventative, holistic and localised services and a strengths-based approach focused on improving individual outcomes – requires a change in mindset from commissioners and policy-makers. Breaking the cycle requires boldness and innovation. And if we get it right, the potential prize is huge.

Policy Live

Exploring policy solutions to some of the biggest challenges faced by the UK

Policy Live is a new event focused on exploring potential policy solutions to some of the biggest challenges faced by the UK. The one-day programme will convene influential leaders and emerging voices from across governments, the civil service, NGOs and the private sector.

Join us on Thursday 12 September to hear optimistic solutions to some of the UK’s biggest policy challenges, forge connections with other policymakers and influencers, and discuss and experience innovative policymaking ideas.

- Hear from insightful speakers from across the political spectrum tackling era-defining issues.

- Engage with keynote speakers on critical topics like the economy, public health, education, the environment, and technology.

- Take part in interactive sessions and hands-on workshops.

- Connect with fellow policy professionals, expand your network and gain new perspectives.

- Enjoy all-day refreshments and a workspace at our central London venue, just a short walk from Westminster

Visit the event website for more information, to see our list of confirmed speakers and to register for your complimentary place.

Event information

- 12 Sep 2024 09:30 – 18:30

- etc Venues, County Hall, London

- Free to attend

Capacity crunch: the biggest challenges facing the next government

Sam Freedman is a political journalist, author and former policy adviser at the Department of Education. He has conducted an analysis of the UK 2040 Options reports on economic growth, health, education, tax and public finances, wealth and income inequality, and power and place. In this report, he draws out the cross-cutting themes that span the UK government’s most pressing challenges.

The UK is in a bad place – stuck in a loop of low growth and productivity, with underfunded and inefficient public services, record low levels of trust in politics and a general sense of frustration from across the political spectrum, regardless of ideology.

But there is nothing stopping us from turning it around by 2040. That’s the timeframe that the UK 2040 Options project is looking to: it has commissioned analysis in topic areas that will be critical to deciding what our future will look like.

There’s a long list of things we could do, it’s just that the nature of our political system makes it so hard to do them. Only by tackling head on these broader cross-cutting political challenges can politicians steer us through our current problems to a more optimistic future. And they need to get on with it, because the list of demands on the state is only going to grow.

- By 2040, there will be much higher healthcare, social care and pensions costs due to an ageing population. Chronic health conditions are projected to affect a substantially greater number of people.

- Decades of underinvestment in capital and infrastructure risk driving future costs in acute crisis management even higher. We can already see this playing out in the NHS and the criminal justice system, among other examples.

- There is a growing number of external risks, including worsening global security following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, growing tensions in the Middle East, and concerns about China. The effects of climate change will increase and we have learned the hard way the need to be prepared for pandemics.

- The rise of the ‘regulatory state’ has meant a big, and largely undiscussed and unplanned, increase in regulatory costs for public and private institutions. There is ongoing pressure for further regulation across multiple sectors – often with good cause.

The UK isn’t unique in this regard. Countries across the world are facing similar challenges, but there are elements of the UK’s political set-up that make them particularly difficult for us to deal with.

- The UK is uniquely centralised. This puts huge operational pressure on the centre, while leaving local government weak and unable to raise its own funds. There are major regional disparities in wealth and productivity that are, in part, driven by this lack of power at regional or local level.

- The UK has a constitutionally extremely powerful executive combined with weak central institutions that struggle to use this power effectively. Government ministers rarely last more than a year or two. Attempts to reform the civil service have been half-hearted at best and it has been left largely as originally designed.

- The Treasury is unusually powerful for a finance ministry and essentially holds veto power over everything that happens in government, meaning it sets the de facto strategy.

- The UK has a highly centralised political culture that is caught up in a super-fast media cycle. This leads to a focus on communications at the expense of policy, which paradoxically creates a loss of trust with the public.

Managing demand for services will require the state to spend more upfront. Some of this can be achieved through better taxation but mostly it requires growth through improved productivity. It will also need more efficient public services through greater investment in infrastructure, technology, and prevention. This is well known and has been for a long time. There isn’t a shortage of ideas about how to do these things, but our structural constraints keep getting in the way. To tackle them effectively, politicians need to confront the ‘meta’ cross-cutting challenges of the way our state works.

The UK needs:

- more effective central institutions that are able to support ministers in decision-making, rather than the haphazard collection of structures that have evolved over centuries

- more capacity at regional and local level, with more operational functions devolved to them and more ability to decide strategy for regional economies and services

- more effective engagement around democratic trade-offs, through greater transparency and accountability, as well as exploring new ways to assess the public-preferred routes through difficult trade-offs

- a clearer framework for regulation, risk and prevention, rather than the entirely arbitrary and poorly evaluated and costed approach we take at the moment.

There are many different approaches politicians could take to create a new political settlement. But we will only get to 2040 in good shape if we have one. What we have now isn’t up to meeting the challenges we face.

Download the full PDF report

How the citizen incubator model could reimagine the way we tackle our most pressing social problems

James Green, founder and CEO of Public Life

The threads of power and place run through everything we are exploring in UK 2040 Options. Understanding how power and place interact, and how they impact people and communities, is critical to understanding how we might make the UK a fairer place to live. This is the first in a series of essays that will explore ideas about how we might use power and place to do just that.

What will life be like in the UK when today’s children reach adulthood? The question Nesta has posed through UK 2040 Options is the same one that is being discussed with growing pessimism at school gates and dinner tables across the country. It is no surprise: hope is in short supply and trust is at a record low.

However, there is reason for optimism. As trust in traditional institutions has fallen into sharp decline, new models of public-led activism, innovation and ownership are on the rise, catalysed by technology. Yet, despite this, the way we design solutions to our biggest public problems has barely changed for centuries, with decisions made by a small number of people in an even smaller number of institutions. This creates an opportunity. If we can get this right, we can inspire a new generation of citizens to lead the way in helping tackle some of our most pressing social issues. If we can’t, there is a risk that declining trust in institutions turns into a loss of the public consent on which their power resides.

The citizen incubator model

For the last twenty years, I have worked in and around public life. I have seen it from the inside, heading up the offices of MPs, and have influenced it from the outside, leading national lobbying teams and creating UK-wide campaigns.

These experiences have led me to conclude that there is a fundamental flaw at the heart of UK public life – it doesn’t actually involve the public. From Whitehall to town halls, the people creating solutions to our biggest social issues are almost never the ones facing them on the ground. This has left the public on the sidelines, disempowered by a system that often sees them as a problem to be solved rather than an asset to be unlocked.

The evidence is clear that public trust and citizen engagement are mutually reinforcing. Yet, as the Institute for Government point out in their in-depth review of the UK constitution, there are “limited opportunities for citizens to shape the decisions that affect their lives in a meaningful sense.” This has contributed to growing scepticism amongst the public in the institutions that represent them. Recent YouGov polling found that 56% of people believe parliament does a bad job of representing their interests, with only 11% saying it did a good or fairly good job. Hansard Society research reinforces this, finding that 50% believe the main parties don’t care about “people like me.”

Creating a new approach that puts citizens in the driving seat has been my obsessive focus over the last seven years. I wanted to rebuild trust and agency, so designed the ‘citizen incubator’ model to both support those facing social issues to invent the solutions they need, and inspire citizens to recognise their own power to lead change. That’s why the approach is not just about ideas. Equally as important are the opportunities thousands get to play their part as active citizens and their impact on the hundreds of thousands reached through their work. In this way the model is as much about incubating citizenship as it is new solutions.

I have designed and delivered multiple programmes using the model, with thousands of citizens and hundreds of organisations involved, and a range of new community-led businesses are now in the world as a result. An independent university evaluation of the last programme using the model found that in its first year alone, it generated a social return of £6.26 for every £1 invested.

The citizen incubator model has three key elements:

- Citizen facilitation. A unique approach that identifies and recruits active citizens facing social issues as citizen entrepreneurs and pays them a living wage.

- Community innovation. A five-phase process that supports citizens to spend a year inventing impactful solutions with thousands locally.

- Funder collaboration. A model that involves funder organisations throughout, with them ready to invest in credible citizen solutions.

This is the story of the most recent citizen incubator programme.

A mission-led approach

Eastlight Community Homes wanted to be bold and invest in a different way in its North Essex communities. As the biggest community-led housing organisation in the country, its board was passionate about putting power firmly in the hands of local people. The citizen incubator model gave them a chance to support them in a radical new way.

The programme I designed involved recruiting 20 Essex residents and paying them a full-time living wage salary to dedicate a year to going from a blank sheet of paper to inventing new solutions with thousands locally. Based in teams in the Essex towns in which they lived, these citizen entrepreneurs took on four community missions. These focussed on the social issues facing them and their communities, informed by polling we had commissioned locally. We wanted to understand how the model worked in different settings so focussed on a range of geographies, from Halstead, a town with a population of 12,000, to Colchester, a city with a population of 130,000.

The citizen entrepreneurs went through a 12 month innovation process. This involved leading ethnographic research to get under the skin of their problem, running workshops across their communities to generate ideas, designing experiments to test the best of those with local people, and finally delivering their solutions on the ground with a six-week pilot. My team provided the support they needed, but they took every decision. The big question was – through this mission-led approach, could citizens with no experience of social innovation invent impactful new solutions to the issues facing them?

To answer that question we commissioned the University of Essex to independently evaluate the programme. They found the model created impactful citizen solutions to complex social problems, strengthened communities by building trust and engagement, and delivered life-changing experiences for the citizen entrepreneurs.

Impactful citizen solutions

The teams created genuinely impactful solutions to the problems important to them. Each was piloted on the programme with measurable impact. The university calculated a collective social return on these pilots of £668,000. The citizen entrepreneurs went on to use this evidence for their funding proposals, with every one going on to win funding and spin out as its own community-led organisation. Crucially, every aspect of the solutions creation, development and implementation were informed by direct life experience of the social issues they were working on.

A great example was Karen and her Colchester team (which included her daughter Jessica), who had taken on the community mission of the cost of living. Their insight was that those who have the least money are often the best budgeters. And they knew that because that had been them. That insight became Trusted, an innovative peer-to-peer money confidence programme, the first of its kind in the UK. The team piloted Trusted on the programme and its impact blew them away. In the space of just six weeks, the ten pilot participants collectively saved nearly £45,000. Trusted went on to secure funding and become its own community-led organisation with Karen and Jessica at the helm. They have run a number of programmes since, all with similar results, and are busily working to scale the model.

Stronger communities

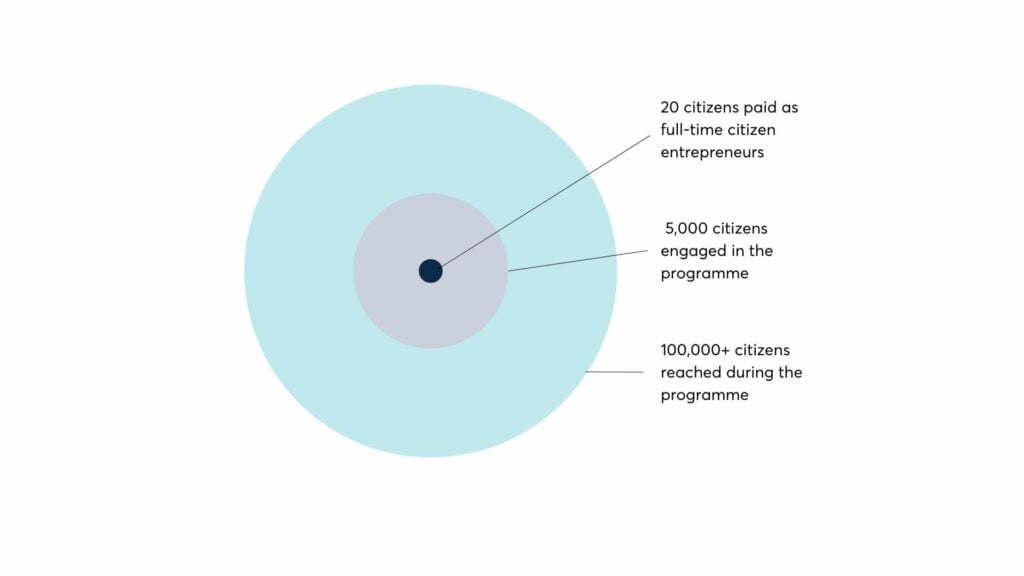

The University found that “the programme created genuine trust and engagement and fostered community in multiple directions and levels.” Over 5,000 local people engaged with the citizen entrepreneurs over the 12 month period, half of them in person. This was a collective endeavour with the community getting involved because it was their friends and neighbours taking the lead and working on issues that were affecting their lives too.

The reach of the programme was also significant. We estimate their work reached over 100,000 people locally. This was important to us as it demonstrated to local people, with tangible relevant examples from their communities, the power they had as active citizens.

The community incubator model has reached over 100,000 people in North Essex

Life-changing experiences

By offering a full-time living wage salary and recruiting without asking for a single CV, we managed to reach people who would never have previously seen themselves doing this sort of work. This included people in low-paid precarious work as well as those who had been out of work for years. We had 100% retention of participants, 67% of the paid community participants went on to better jobs in the months immediately following the programme (defined as either better-paid work or leading the solutions they had invented), and there was a 60% average increase in networks for participants as a result of the programme.

We measured a range of self-reported outcomes at the beginning and end of the programme covering dimensions including mental health and wellbeing, enhanced employability, confidence, skills, and social isolation. Questions were based on the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scales, a widely used methodology for measuring wellbeing that has been validated in a range of settings. As a cohort, there was a positive and statistically significant shift across almost all self-reported outcomes, demonstrating the direct impact of the programme on different aspects of the participants’ lives.

Taking into account all of these impacts the university calculated that in its first year alone the programme generated a social return of £7.5 million. And this “conservative figure” only takes into account its impact during the year it was active. It does not include the programme’s longer-term impact on the participants, communities or of the solutions they created. “This means”, the university concluded, “that for every future year the social impact of the programme is likely to increase considerably.”

A new vision of public life

Imagine if citizens in communities up and down the UK were supported in this way to invent new solutions to the social issues facing them. Not only would we have a wide range of new community-led solutions to some of our most intractable social problems, we would also have hundreds of thousands of citizens involved in the process of creating change. The scale of impact could be transformational.

At the local level, new social businesses would be making a tangible difference at the grassroots, created by citizens for citizens. And at a national level, a different relationship would begin to emerge between citizens and the institutions that shape their lives, rooted in meaningful partnership. With hundreds of thousands of citizens involved and millions reached, public life would feel very different. All of us would gain a deeper understanding of how problems are experienced on the ground, benefit from the insights and solutions that can only come from life experience, and see citizen-led change catalysed in ways we would never have predicted. This would be a different type of public life – one boldly led by the public.

The most wealthy need to pay more tax: here’s what the UK can learn from the rest of the world

John Craven, Executive Officer at System 2

UK 2040 Options recently analysed the current state of wealth and income inequality in the UK. The experts they engaged with were clear that taxation is a key factor that is ripe for reform.

In the twelve years I spent working in financial markets, wealth management and tax consulting all over the world, I gained valuable insight into how businesses and rich individuals respond to the incentives that tax systems around the world offer them. More recently, as a teacher, a charity CEO and the Director of the Social Mobility Commission, I’ve seen firsthand the impact that high levels of inequality have on society.

This blog draws on these experiences and explores some realistic options for policymakers to reduce inequality, which have been tried and tested in other countries.

It’s not inevitable: a reflection on the international context

The IFS sets out how poor tax design in the UK is a major challenge. Certainly, if we were able to redesign the tax system from scratch, it could reduce inequality and damaging distortions, while improving productivity and economic growth. But in reality, we know that political constraints mean that reform is often slow and incremental, and it can take time for new ideas to gain acceptance.

Whenever a new tax is proposed, or the reform of an existing one is recommended, those who are adversely affected lobby hard to maintain the status quo. Practical proposals, sensible reforms or attempts at simplification (such as the “Pasty Tax”) are often dismissed as impossible to implement, unfair when considered in isolation, or likely to result in damage to the economy. The result is tax inertia. Instead of optimising policy to minimise distortions, improve incentives and raise productivity, policymakers make fewer changes, instead using devices such as fiscal drag to increase revenue.

The resulting set of income and wealth taxes in each country throws up some surprising differences. What some consider to be radical policies in the UK are uncontroversial elsewhere. For example, unlike the UK, Australia (where I am currently based) has no inheritance tax and the state pension is means-tested.

How ultra-high-net-worth individuals avoid tax

As a director at a global wealth management firm, that included a Swiss private bank, I oversaw complex investments for wealthy clients, spending much of my time in cities such as Dubai, Geneva, London, Monaco and Paris. I often met ultra high-net-worth clients, with at least $25-50 million in net assets. I listened as advisers explained how they could avoid tax.

Most sought to minimise their tax liabilities where it was clearly legal and involved limited disruption to their lifestyle. If it was legally or reputationally risky, or hard – such as requiring a move abroad – they were more likely to decide to stay and pay the sticker price taxes. Some were happy paying local taxes on income and capital “in full” since the country had enabled them to generate that wealth. A few, particularly those with fewer ties to the country, sought to pay as little as possible, even when that involved taking risks or moving to a tax haven.

One British man I met in Monaco had sold his UK business and was there for five years to avoid paying millions of pounds of UK taxes on his gain. He could still visit the UK but only for a limited number of days each year. When I first went to his apartment, he would stand on his balcony overlooking the harbour, and tell me how lucky he was. The third time we met he told me how much he missed his family and couldn’t wait until he could move back to spend more time with his grandchildren. I’m sure that if the rule had been ten years not five, or he was allowed back in the UK for even fewer days, he would never have left England and paid his taxes there. The set of choices we gave him incentivised him to avoid paying tax here.

To the extent international law permits, we can start by changing that.

But we must go much further than simply tightening up rules on the number of days that small numbers of wealthy UK citizens who become non-resident can spend in the UK without triggering tax implications. Understanding how other countries have introduced similar taxes can help us overcome the inevitable resistance that the threat of a new tax brings.

Seven practical ideas for policymakers to reduce inequality

1) Increase the Stamp Duty Land Tax surcharge for non-UK-residents purchasing UK residential property from 2% to 15%

International ownership of housing can increase inequality. It can reduce the supply of housing available for locals, increase rents and house prices and make it harder for young British people to own their own home. Hamptons estimated that in 2023, 24% of homes sold in Greater London went to international buyers, rising to 45% of those in prime Central London.

Other developed countries have taken much bigger steps than the UK to deter foreign ownership, or at least to raise greater taxes from it. At one extreme, Canada has banned foreign purchasers altogether, until at least 2027. The situation is similar in New Zealand, with some exceptions for temporary ownership of newly built housing. To buy in Switzerland, foreigners need a permit, only 1,500 of which are issued each year through cantons. Singapore recently doubled the additional stamp duty paid by foreigners buying residential property to as much as 60%. In Australia, foreign buyers will soon be hit by extra fees and taxes totalling 14%-17%.

In comparison, the UK charges foreign buyers a mere 2% supplement, with few restrictions on owning property in the UK. Increasing the rate to 15% could deter overseas buyers, freeing up property for local buyers, while bringing in revenue from the most determined. Halving the rate for new-build flats could prevent the risk of this policy reducing the housing supply.

2) Increase the higher rates of Stamp Duty Land Tax for those purchasing additional existing homes from 3% to 6%

It is not just overseas buyers that compete for property with first-time buyers. Local residents also acquire second homes and investment properties. Singapore citizens and permanent residents buying their second or subsequent properties pay a 20%-35% supplement. In comparison, the UK charges those buying additional properties only 3% more. Doubling this to 6% for existing properties would bring in much-needed revenue. Exempting new-build flats could prevent the risk that this could reduce supply.

3) Create a new Annual Property Tax on market-based hypothetical rental income, charged to owners of all homes, except UK resident owner-occupiers

One way to ensure properties are more likely to be rented is to tax vacant properties as though they are let. Many countries take this approach. Property owners in Switzerland must pay income tax on a property’s perceived rental value, deducting mortgage interest payments and maintenance costs, in addition to taxes on the value of property and wealth. Singapore applies a tax on property ownership, whether the property is occupied by the owner, rented out or left vacant. A tax rate of 12%-36% for non-owner-occupiers is charged on the estimated gross rent of the property with owner-occupiers charged less. In the UK, council tax is the closest to a property tax, with properties put into one of eight bands based on values in 1991. The IFS recently set out how council tax is highly regressive with respect to property values and leads to increasingly arbitrary tax bills.

While some councils are doubling the council tax on second homes and empty dwellings, a more consistent approach nationally would be to create a new Annual Property Tax on a market-based hypothetical rental income. This could be charged to owners of all homes at marginal income tax rates, except UK resident owner-occupiers – so would be paid by owners of second homes, rental properties and vacant properties. Those that are rented out would pay tax on the actual rental income achieved if higher and could deduct relevant costs. If not rented for at least six months of the year, no deductions would be allowed, and a flat 45% tax rate on the hypothetical value would be applied.

4) Prevent individuals with assets in ISAs above £100,000 at the beginning of a tax year from investing in a new ISA that year

Most developed countries offer tax incentives to save for retirement, but very few are as generous as the UK in offering easy access savings accounts sheltered from tax. ISAs allow UK taxpayers to invest £20,000 each year without paying any income or capital gains tax on profits. Those with lower incomes and wealth typically have lower total savings and do not benefit from this significant tax break.

At the same time, the more affluent have accumulated significant savings, returns from which are permanently sheltered from tax. Over 4,000 people have ISA savings that exceed £1 million. It would be considered unconventional and unfair to make ISA savings above a given threshold taxable again. Preventing people with ISA savings above £100,000 at the beginning of the tax year from opening a new ISA that year would mean they would need to pay income and capital gains tax on investment returns from the savings they are no longer able to put into the ISA.

5) Create a new Retirement Savings Allowance tax charge on pension assets above £500,000 at age 70

A common definition of a pension is that it provides those who are retired with a regular income, not that it is a savings vehicle or investment account. Indeed, until it was abolished in 2011, pensioners had to use their (defined contribution) pension savings to buy an annuity, which provided a fixed income for life. Yet, for many wealthy investors whose pension savings exceed the £1,073,100 Lifetime Allowance, their pension is not used to generate an income on retirement but is part of their inheritance tax planning strategy and used as a store of wealth. As such, the upcoming abolition of the Lifetime Allowance is an unnecessary reduction in tax for some of the most wealthy in the country.

The Lifetime Allowance was introduced in 2006, capping the amount of pension savings that can be built up without incurring a tax charge, typically of 25% (it was reduced to 0% this tax year). The limit was repeatedly decreased in real terms but is now due to be abolished altogether in April 2024. The changes reduce the potential tax liability of those with pension savings exceeding the limit when they retire and hence increase inequality. Meanwhile, Australia is raising pension taxes, not abolishing them, introducing a new 30% tax on pension balances above AUD$3 million (roughly equal to £1.56 million) from July 2025.

There would be challenges in reinstating the Lifetime Allowance, so instead, a new Retirement Savings Allowance (RSA) could be introduced set at £500,000, but only applied on savings, not annuities (providing a fixed income) that have been purchased or defined benefit pensions. The vast majority of people are unaffected, and those who use their pensions as intended — to generate an income rather than to store wealth or avoid inheritance tax – don’t lose out. To maximise the impact, while giving people time to buy an annuity at a time that suits them, this RSA test could be applied to all with at least a year’s notice at age 70 or later.

With pensions, there is always a lot of detail to work through, so I don’t pretend this comes close to covering it!

6) Create a new 1% wealth tax charged on net assets above £2 million

In 2020, the Wealth Tax Commission published a report setting out how a one-off wealth tax could be designed as an exceptional response to the fiscal costs of the Covid-19 pandemic. It set out how a 1% tax on individual assets above £2 million could raise £80 billion over five years. It added that a more permanent “annual wealth tax would only be justified in addition to these reforms if the aim was specifically to reduce inequality by redistributing wealth”.

There are additional challenges with an annual wealth tax, including measuring hard-to-value assets, and fears that it would drive away mobile wealthy individuals, damaging the economy. Countries such as Switzerland have shown these can be overcome. All Swiss cantons impose a wealth tax on net assets, even for low levels of wealth. For example, for net assets above 82,200 francs, Geneva has a rate of 0.149%, with marginal rates rising as wealth increases, and exceeding 1% in some cantons. It generates as much as 3.8% of total taxes in Switzerland.

7) Create a new British Citizen Tax, mirroring the wealth tax, payable by all wealthy British citizens living overseas

One issue with a Wealth Tax is it could incentivise wealthy British citizens to move overseas to avoid it, which would reduce the tax raised. In the US, citizens are fully subject to US tax on their worldwide income and gains, no matter where they live, unless they renounce citizenship. Issues such as the administrative burden it creates for those of more modest means, and double taxation of income, means that some specialists say it would be unwise for the UK to replicate it. Instead of taxing income and capital gains, a wealth tax payable by those British citizens living overseas with net assets above £2 million could overcome many of the problems, if it could be designed in compliance with international rules. Those with assets below that would need to make a simple annual declaration listing valuable assets and provide copies of local tax returns to HMRC. Wealthy UK citizens living permanently abroad would need to renounce citizenship if they wanted to avoid the tax.

Some of the revenue from these new taxes could be used to reduce other taxes, both to reduce inequality further and to improve the efficiency of the system. Personal allowances could be increased to improve incentives to work and raise post-tax incomes of lower earners. Incentives for higher earners could be improved by reversing the removal of child benefits and the personal allowance from higher earners that currently creates very high marginal tax rates of 62% or more. Finally, a permanent halving of all basic levels of stamp duty would increase transactions, improving the geographic mobility of workers and removing the incentive to move as infrequently as possible.

Mythbusting: reform is not impossible

I acknowledge that some of the above is necessarily a simplification of a complex system. I don’t underestimate the challenge involved in creating an environment that allows for major change.

But I hope that at least by showing how other countries use similar taxes, it destroys the myth that these taxes are impossible to implement in the UK. And that this brings forward the day we might move to a fairer tax system that reduces inequality.

John Craven is Executive Officer at System 2, a charity set up by The Behavioural Insights Team and Nesta. It aims to solve complex social problems by bringing together behavioural science, systems thinking and insights from deep collaboration with those with lived experience, to co-design, test and scale practical solutions.

He is also an Honorary Fellow in Educational Equity at the University of Birmingham. Formerly he was a Director of Global Wealth Management, Bank of America, and was the former Director of the Social Mobility Commission in the UK.