Health and social care: the ideas

Children born today will be taking their first steps into adulthood in 2040. What will life in the UK be like for them, according to current trajectories? What policy options do we have now that can influence or change that trajectory for the better?

When we started UK 2040 Options in June 2023, a year out from the General Election, we asked health and social care experts two simple questions: what are the greatest issues facing the health and social care systems; and what interventions might best help to improve them by 2040? As health is devolved, we asked experts to consider these issues in relation to England.

The results highlighted the myriad of challenges that are facing England’s health and adult social care systems and sparked a year-long dialogue with experts, emerging thinkers and practitioners about both where there is established consensus on the issues and way forward, and where there is fertile ground for new ideas.

With The Health Foundation, we assessed the fundamental facts that underpin the NHS and adult social care systems. We then highlighted the big choices that the new UK Government faces as a result. This report focuses on some of the interesting, innovative policy ideas that emerged.

It is well established that between now and 2040 the UK Government will need to grapple with the funding, structures and big workforce challenges that the NHS and social care systems face. Others, such as The King’s Fund, The Health Foundation, and Nuffield Trust are looking at those questions in detail. The ideas set out here are intended as additive – highlighting some policy ideas that, in a new, mission-driven government, have the potential to improve outcomes, regardless of the path taken on the big structural and funding questions. They’re not a set of recommendations, and nor do they represent a ‘strategy’ to ‘fix’ the NHS, but they should serve as food for thought for policymakers looking to innovate.

The eight ideas that follow in this report:

- Overhaul the policy approach to obesity: tackling poor diets upstream by introducing mandatory health targets for supermarkets

- Tackle alcohol-related harm head-on: through the introduction of minimum unit pricing

- Reform the Treasury’s fiscal framework to prioritise prevention: introducing a new category of public spending for prevention

- Make NHS staff wellbeing a strategic priority: improving data collection and transparency, testing wellbeing interventions, and scaling the ones that work

- Pave the way for an AI health revolution: standardising patient records, and establishing a new National Data Trust

- Ramp up the use of digital mental health services: through expanding access to, and effectiveness of, internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (eCBT) and other digital tools

- Stem rising demand in social care by slowing ageing: through preventing falls and improving physical activity in older people

- Proactive and streamlined support for unpaid carers: through targets and incentives

Economic growth: the ideas

Children born today will be taking their first steps into adulthood in 2040. What will life in the UK be like for them, according to current trajectories? What policy options do we have now that can influence or change that trajectory for the better?

Almost all of the UK Government’s options to improve outcomes by 2040 will be shaped by our economic fortunes. Economic growth is a lynchpin for improved standards of living and social progress, and bolsters the tax receipts that fund better public services. Policy that secures higher productivity and growth enables governments to pursue ambitious policies elsewhere to keep our citizens healthy and look after those who are not, provide good educational opportunities, to both resist and build resilience against a changing climate, and more.

But growth has been elusive for the UK in recent years, and particularly since the financial crisis of 2007-2008. The consequences of this continue to reverberate across the economy; the gap between where we are headed and where we could have been, based on pre-Global Financial Crisis trends, is stark.

We’ve convened the brightest and best economists and thinkers in the UK and beyond to discuss the issues, trade-offs and ideas for reversing the trend. We’ve already examined the fundamental facts and choices and here we highlight some of the many ideas raised by those at the forefront of growth economics.

Focusing on four areas that came up time and time again – our institutions, land use, labour markets, and business productivity – some of the ideas are big, and some are small. Some aim to add to the literature on well-trodden ground, and some are more novel. They don’t aim to provide a comprehensive strategy for ‘fixing’ growth, but we hope all are thought provoking.

The nine ideas that follow in this report are:

- Establish an enduring new independent growth institution

- Empower functional economic areas by establishing regional and local governments in England with a route to devolution and fiscal agency

- Tackle the housing crisis by moving to a zone-led planning system that simplifies the rules for developers

- Improve land use efficiency by introducing a land value tax

- Reduce labour market inactivity by harnessing data and AI to proactively support individuals

- Improve the transparency of the labour market to improve job quality

- Introduce regionally-specific migration routes

- Create ultra-low-cost energy zones to support industry

- Embrace experimentation by developing a productivity innovation fund to understand the most effective interventions

Net zero: the ideas

Children born today will be taking their first steps into adulthood in 2040. What will life in the UK be like for them, according to current trajectories? What policy options do we have now that can influence or change that trajectory for the better?

The UK has a strong track record of leadership on net-zero targets, but this is a country that is veering substantially off-track for future carbon budgets unless it massively accelerates the pace and breadth of its decarbonisation.

Through Delphi exercises, workshops and interviews, we’ve asked experts two questions: what are the biggest priorities facing the UK Government as it seeks to deliver on climate targets, and what interventions could deliver on these priorities and get the UK back on track by 2040, ahead of the Government’s target to reach net zero by 2050? It’s worth being explicit that targets are a proxy – a necessary one – for the things we really care about. In this case, stabilising the impacts of global warming to reduce global harms, and making the UK better off, greener, more comfortable and healthier as we do so.

We’ve already distilled the challenges and priorities into the fundamental facts and the big choices for Government to grapple with. This paper is the third in our series, and focuses on the ideas that could help deliver that better, greener, healthier UK by 2040, and beyond.

The ideas presented here are not intended to form a comprehensive strategy across all priority sectors, nor are they a clear-cut set of recommendations. Instead, they are intended to be practical, thought-provoking policy ideas which could support the trajectory to net zero.

The ten ideas that follow in this report are:

- Bring citizens into the key issues: launch a national engagement campaign on net zero

- Support an effective market for green products and services: increase information transparency for consumers using green subsidies

- Explore an alternative delivery model for home retrofit: coordinate household decarbonisation street-by-street

- Increase centralised planning for major infrastructure: make NESO a system architect

- Increase efficacy of land use for environmental outcomes: develop a national rural land use framework and use it to underpin farming payments

- Make better use of carbon pricing mechanisms: expand the scope of the UK Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS)

- Harness the market power of state funding: amend government procurement to require net-zero carbon construction materials to reduce embodied emissions

- Change incentives and increase innovation in energy markets: reform the structure of the energy retail market to support household decarbonisation

- Incentivise households to decarbonise when they’re moving house: reform Stamp Duty Land Tax to become an energy-saving stamp duty

- Show leadership on the impacts of climate change: develop and legislate adaptation targets

Education: the ideas

Children born today will be taking their first steps into adulthood in 2040. What will life in the UK be like for them, according to current trajectories? What policy options do we have now that can influence or change that trajectory for the better?

When we started UK 2040 Options in June 2023, with 12 months to go before the general election, we asked more than 60 education experts two simple questions: ‘what are the greatest issues facing the education system?’ and ‘what interventions might best help to address them by 2040?’ As education is devolved, we asked experts to consider these issues in relation to England.

The results highlighted the range of challenges facing England’s education system, some well-known, some more surprising.

It sparked a year-long dialogue with experts about where there is consensus on the issues and way forward, and where there is fertile ground for new ideas.

With the Education Policy Institute, we set out the fundamental facts about the education system that policymakers need to know. We then worked with experts to dig into the big choices the new UK Government would face. This report focuses on 10 of the most interesting, innovative policy ideas that have emerged during this process.

What follows is not intended as a set of Nesta recommendations, but exciting ideas from some of education’s brightest minds, offering food for thought for policymakers looking to innovate in an area of policy that is vital for improving outcomes between now and 2040.

The 10 ideas in this report are:

- Build a professional development system for the early years: raising the quality of training and development early years practitioners receive throughout their careers.

- Reshape school structures: a single system to run and improve schools: blending the best of the maintained system and the trust-led system together.

- Make teaching a 21st-century career: backing innovation in working practices to increase flexibility and reduce workload.

- Decouple the process of mainstream Education Health and Care Plans from special school admissions: enabling mainstream schools to understand and meet a wide variety of learning needs.

- Develop the next generation of integrated family support services: building on Sure Start and Family Hubs, and testing, learning and iterating to continuously meet the needs of users.

- Protect young people’s mental health: introducing legislation to create ‘safe phones’ for under 16s.

- Expand enrichment to all young people: opening schools from 8am to 6pm.

- Make kinship care the first port of call: allowing children who cannot live with their parents to stay in their family networks wherever possible.

- Revive youth apprenticeships: targeting apprenticeships at young people, and offering a different approach for adults upskilling and reskilling.

- Increase the supply and demand of sub-degree qualifications: introducing exit qualifications after each year of university study

Ideas to propel us to a better 2040

By Alexandra Burns

Over the last few years, the public debate about politics and policy has often felt bleak. With public services struggling to meet demand, a fragile economy and an increasingly unstable world, it’s easy to see why optimism about the future has been lacking.

But what would it take to change course?

UK 2040 Options has worked with around 300 experts in an effort to lift our collective heads from the crisis and look forward. A child born today will become an adult in the early 2040s. We’ve examined what the country will look like for them if things stay the same, and what we could do now to alter that trajectory for the better.

First, we assessed the fundamental facts that underpin each of the topics. We then highlighted the big choices that the Government faces as a result. These reports now focus on policy ideas. In doing so, they aim to bring to the fore some of the interesting and potentially impactful policy ideas that experts have suggested to us over the past year.

Across areas critical to the country’s future – economic growth, health, education and the transition to net zero – we found a high degree of consensus about both the issues and the big, difficult choices facing the new Government. But we found hope and new, innovative ideas too. The four reports we’re publishing today aim to be honest about the challenges and bold about the solutions.

From the introduction of safe phones for under-16s to setting supermarkets targets for the healthiness of the food they sell, from harnessing AI to reduce labour market inactivity to decarbonising homes street by street – the ideas aren’t lacking. Now is the time to debate them and their trade-offs honestly. Our hope is that they provide food for thought for those engaged in designing the country’s future.

Continue the conversation at Policy Live on 12 September – registration is open now.

Turning the tide on place-based health inequalities

Luke Munford, Senior Lecturer in Health Economics, University of Manchester

The threads of power and place run through everything we are exploring in UK 2040 Options. Understanding how power and place interact, and how they impact people and communities, is critical to understanding how we might make the UK a fairer place to live. This is part of a series of guest essays that explores these themes.

England is a deeply unequal country. Health, wealth, and opportunities to thrive differ greatly depending on where we live and work.

The relationship between health and place can be considered in terms of the interplay between who lives in a place, what the place is like and the wider public policy context. Often, individual circumstances interact with the place where people live to exacerbate or reinforce inequalities in health outcomes.

In this piece, I highlight the worrying statistics that show the level of health inequality in England and why policymakers must consider a hyperlocal approach. I also outline the policy options that local and central government have available to help tackle place-based health inequalities.

The UK has wide place-based health inequalities: and they are growing

The UK ranks among the highest in terms of regional economic inequalities among OECD countries. The north of England bears the brunt of these inequalities, with lower economic productivity as well as lower life expectancy than the south of England. Nationally, coastal communities grapple with a higher burden of ill-health and substance misuse.

Our analysis of the most recent data shows that on average, males living in the most deprived areas of England are expected to live 9.7 fewer years than males in the least deprived areas. Females living in the most deprived areas can expect to live 8 fewer years than females in the least deprived areas.

These gaps are even bigger when we consider healthy life expectancy, an estimate of lifetime spent in very good or good health. Males living in the most deprived areas have a healthy life expectancy that is 18.2 years lower than males living in the least deprived areas. Females living in the most deprived areas have a healthy life expectancy that is 18.8 years lower than females living in the least deprived areas.

Worryingly, there is a downward trend in life expectancy for those living in the most deprived areas meaning that the gaps between the most deprived and least deprived areas have been growing over time.

“Despair” is not uniformly spread throughout England

In 2015, a phenomenon coined ‘deaths of despair’ emerged in the US, highlighting an increase in deaths caused by drug and alcohol misuse as well as suicide. The underlying cause of these deaths in the US is long-term economic disadvantage: low levels of education, income inequality and poverty, as well as a breakdown of community and social structures, including insecure and low-paid jobs, income inequality, housing evictions and workplace automation.

In a study that my team at the University of Manchester recently conducted, we used the latest available data from England to see whether there was a similar trend. It showed us that between 2019-21, 46,200 lives were lost to deaths of despair (equivalent to 42 each day) with an average rate for England of 34 lives lost per 100,000 people.

But below this average hid significant regional disparities, mapping on to what we know about place-based inequality. The North East had the highest burden, averaging 55 deaths of despair per 100,000 people, but in stark contrast, London’s rate was very low, with around 25 per 100,000. Despair therefore seems to not be uniformly spread throughout England: of the 20 local authorities with the highest rates of deaths of despair, 16 were in the north – but none of the 20 areas with the lowest rates were. These are stark and unacceptable differences.

To understand what might be driving these gaps, we identified a number of area-level factors that were associated with the elevated risk of deaths of despair. These included high unemployment rates, higher proportions of White British ethnicity, solitary living, higher rates of economic inactivity, employment in elementary occupations, and whether the community was urban (compared to rural). This also emphasised that deaths of despair are not inevitable – but rather a tragic consequence of inequitable resource distribution.

Deprivation interacts with place, amplifying its impact

While deprivation and the lack of resources available to people and places are key drivers of health inequalities, there is evidence that region-level deprivation interacts with and amplifies the effect of small area deprivation. We can see deeper health inequalities at a hyperlocal level: this is a phenomenon that we have called ‘deprivation amplification’.

We see this throughout England. Persistent inequalities, evolving over recent decades, have led to the creation of ‘left-behind’ communities. While the use of the phrase left-behind has generated some controversy, it reflects that a set of neighbourhoods and communities have higher levels of need and have largely been forgotten by national policy. There are 225 left-behind neighbourhoods, which are mostly found in post-industrial areas in the north of England and the Midlands.

Again, this has an impact on health outcomes: in left-behind neighbourhoods, men live 3.7 years fewer than average and women 3 years fewer. Both men and women in these neighbourhoods can expect to live 7.5 fewer years in good health than their counterparts in the rest of England, and there is a higher prevalence of 15 of the most common health conditions, even when compared to other deprived areas. This has an economic impact: individuals are twice as likely to claim incapacity benefits due to mental health-related conditions when compared to England as a whole.

This deprivation amplification was particularly acute during the Covid-19 pandemic. Across England, the most deprived areas had the highest rates of Covid-19. But when deprived areas in the north were compared to areas that were equally deprived in other parts of England, we found that northern areas had significantly higher rates of mortality. We found that deprivation alone could not explain these very stark differences. And again, people living in left-behind neighbourhoods in the early stages of the pandemic were 46% more likely to die from Covid-19 than from those in the rest of England.

Options for a more equal England

Interpreting the complex interrelationships between health and place relies heavily on the availability of high-quality data and the definition ‘place’. However, the way that we currently measure the health of a place is based on geographic definitions that are not always meaningful when it comes to supporting decision-making about how to improve health.

For example, Liverpool has the fifth-lowest life expectancy for males if we consider local authority averages. Yet of the 62 middle super output areas (MSOAs) that make up Liverpool, 10 of them have above the national average male life expectancy. Conversely, not all MSOAs within the local authorities that have the best health outcomes experience the best health. For example, based on census data, 12% of areas within Richmond on Thames (the local authority with the highest life expectancy) reported below average levels of very good or good health.

Therefore, if we base funding decisions solely on local authority averages, we mask really important variation that tells us about the health of communities and where services might be needed.

We need to tackle the hyperlocal differences in health outcomes, as well as the between regions and between local authority differences. But the way policymakers currently think about place-based health inequalities is insufficient, as decisions are based on their understanding on averages of disparate areas. And the way that most people conceptualise ‘place’ is very often different to how geographical boundaries are drawn. For example, most people have no idea which MSOA they live in: instead, we tend to define where we live through key landmarks.

We can see this insufficient consideration of place play out in the previous UK Government’s Levelling Up agenda. Our research has previously raised concerns around whether funding is allocated equitably. Around £125 million was allocated to England in the first round of the Community Renewal Fund (one of the first flagship ‘levelling up’ funding pots). However, when a ‘fair share’ funding allocation was created (based on the UK Government’s own formula) and compared to the actual allocation of funding, large place-based inequalities emerged. The North East received £13.4 million less than expected based on its resilience score. At the other end of the scale, the South East received £3 million more from than expected. Overall, analysis showed no significant correlation between need and actual Community Renewal Fund allocations.

The implication of our work is therefore clear: preventive policies must be geographically tailored. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to fixing regional inequalities, and knowing where the hotspots of poor health really are will mean that policymakers can target funding in a much more nuanced way.

We have set out a series of policy options below. Devolving greater decision-making powers and funding to local and regional governments offers one avenue for delivering bespoke solutions. Greater powers are needed for Metro Mayors to direct financial, health, and community resources towards the areas hit hardest by unfair health inequalities. This is underway in Greater Manchester and the West Midlands, with their ‘trailblazer deal’, but this new data highlights the urgent need to accelerate the devolution of place-based powers.

However, the national policy context – prioritising equitable access to economic opportunities, the labour market, and housing – remains paramount in reducing health inequalities by tackling the social determinants of health. This has been shown to be successful in the past in the UK at reducing inequalities in life expectancy, infant mortality and mortality at age 65. Tackling these socio-economic factors requires interdepartmental collaboration, cross-party working and a long-term commitment to levelling up. The responsibility falls across Government to ensure health is embedded in all decisions aimed at reducing inequalities.

Options

What Westminster can do

- A national strategy developed to reduce health inequalities through targeting multiple neighbourhood, community and healthcare factors. However, this needs to be allocated based on need, so that more deprived and left-behind communities receive their fair share.

- The impact on health, and health inequalities, should be taken into account when making all government decisions, regardless of which government department is making the policy.

- An increase in NHS funding in more deprived local areas (including left behind neighbourhoods) to reduce healthcare inequalities.

- Long-term ring-fenced funding put in place for targeted health inequalities programmes, and focussed at the hyper-local neighbourhood level.

What mayoral/combined authorities and local authorities can do

- Local governments should have increased freedom over their spending to ensure it is used in the best way to tackle health inequalities. In particular, following on from the Health Foundation work, local authorities should utilise hyperlocal data to identify the areas with the highest burdens of disease and use this to target services within their jurisdiction.

- Consistent and long-term financial support should be ring-fenced for communities to engage in neighbourhood-based health initiatives. For example, a Community Wealth Fund, which, if implemented, could offer a means of improving social infrastructure and empowering communities by placing neighbourhoods at the heart of decision-making.

- Programmes developed to increase community engagement to better understand and identify the issues and barriers faced by individuals, and thereby improve the quality of local services.

- Set up community consultation processes in left-behind neighbourhoods to identify the issues facing local communities.

What local government and communities can do

- Fund health initiatives that increase the level of control local people have over their life circumstances, such as the community piggy bank.

- Put community engagement which builds social cohesion, networks and infrastructure at the heart of health delivery.

- Help communities to take ownership of community assets facilitated by sufficient help and support from national and local government.

- Support and incentivise residents to make the most of community assets and maintain their participation through schemes such as lower transport costs.

- Existing services should be redesigned to respond to specific challenges within an area.

If we get this right, there is much to be gained. Not only will it improve the lives of millions of people living throughout England, it will also bring significant savings to the taxpayer. If the health outcomes in local authorities that contain left behind neighbourhoods were brought up to the same level as in the rest of the country, an extra £29.8 billion every year could be put into the country’s economy.

Fixing health inequalities must be a moral urgency for this new UK Government.

Dr Luke Munford is a Senior Lecturer in Health Economics at the University of Manchester and deputy theme lead for Economic Sustainability within the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration in Greater Manchester (ARC GM). He is a quantitative researcher who uses existing data to understand the causes and consequences of health inequalities, with a strong emphasis on place, including focussing on the interactions between people and place. He is also academic co-director of Health Equity North. Health Equity North is a virtual institute focused on place-based solutions to public health problems and health inequalities, bringing together world-leading academic expertise from leading universities and hospitals across the North of England.

Navigating policy complexity: a Delphi method approach

By Ben Szreter, Rachel Carter and Esme Yates

The Oracle of Delphi in Ancient Greece was considered a powerful source of prophecy and insight. Being able to predict the future would, of course, be the ultimate tool for policymaking. But while this is impossible, using a technique named after this ancient oracle – the Delphi method – could be an underutilised asset in policy development.

A Delphi approach can help identify people’s ideas about the future and calibrate those ideas against each other. The unique selling point of the Delphi method is that group decisions and analysis – without the biases that come with group hierarchies – can be better than an individual’s alone. This is as true in policy as in other areas and could be especially pertinent in complex policy landscapes where traditional approaches may fall short.

There have been examples of the Delphi method being used in policymaking from the 1970s, but its use has not been widespread. For example, it has previously been used in forecasting (on topics such as public policy issues, economic trends, health and education), and to help reach expert consensus in health-related settings, such as in the development of medical guidelines and protocols.

In the UK 2040 Options project, we have set out to draw on collective wisdom as we consider policy options that will get the UK to a better place by 2040. In some instances, we have used an adapted Delphi process to draw on a wide range of expert perspectives, which has given us a large funnel through which to filter the wide range of issues and ideas that we are exploring.

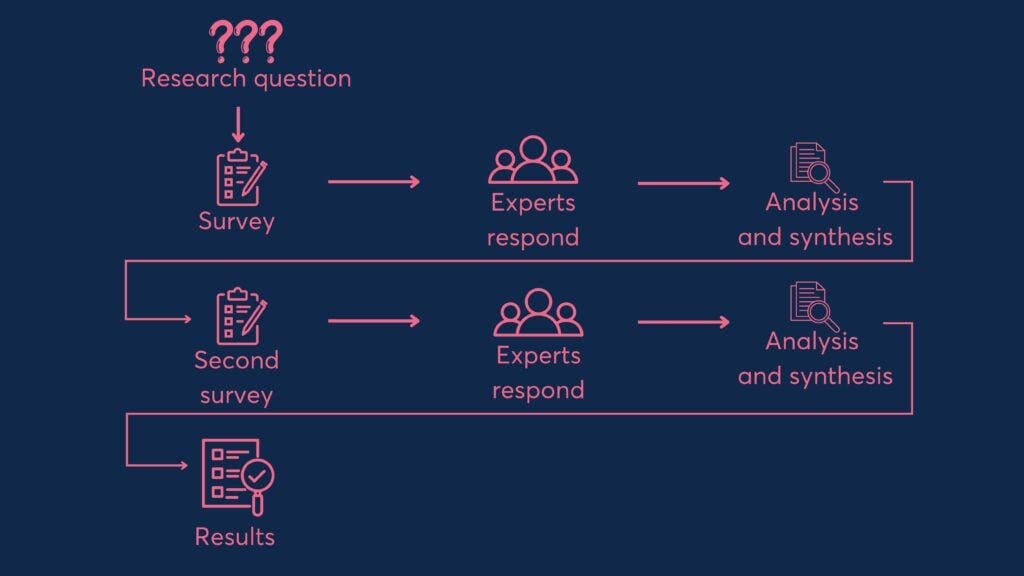

What is a Delphi exercise and how have we run them?

Our Delphi exercises included two rounds. In round one, we asked respondents about the issues and interventions that could impact the topic in question in the UK (such as economic growth) and to rank their responses by importance or potential impact. In round two, we fed these issues and interventions back to the respondents alongside their average importance or impact scores from round one, before asking the experts surveyed for their final judgement. Opinions of all experts were kept anonymous throughout.

The final output is a list of policy issues and interventions, ranked by the scores given by experts in round two.

This process can be seen in the below diagram.

How we’ve used the Delphi method to crowdsource expert views

We have run Delphi exercises on policy topics such as growth and productivity, education, health and net zero. In our adaptation of the Delphi method, we aimed to capture the multifaceted nature of policy issues surrounding various major policy problems in the UK.

Across these Delphis, we have been able to engage with a diverse group of more than 250 experts in total, identify well over 100 critical issues and propose over 900 potential interventions. Using this method has allowed us to get much richer information from experts and emerging thinkers, in a more useable way, than a traditional survey or roundtable alone.

What we gained from using Delphis in a policy context

The Delphi process is a good way to cast a wide net for different views and perspectives on a particular topic. It allowed us to quickly identify the most important issues that there is expert consensus around, as well as pinpoint a wide set of possible interventions.

This helped us to focus subsequent in-person discussions on policy priorities around areas that had been identified as being of the most concern and gave us an understanding of where there is convergence in opinion (the “no brainers”) and where there is divergence (a potential choice for policymakers to make). The suggested interventions also acted as a spark for discussions with experts around trade-offs, the feasibility of implementation, and where government attention should focus next.

All of this provided rich and invaluable insight into specific policy areas, which we were able to draw on and distil in our public-facing research. You can see examples of how we used the outputs of the Delphi process in our education, health and wealth and income inequality ‘Choices’ series.

Insights we gained into the Delphi model

Participants were able to comment on the user experience of the Delphi, and provide feedback on the method and approach. From this, we were able to identify a number of key considerations.

- The wording of the questions needs to be succinct and well-considered. When working with people that have, at most, 10 minutes of focussed time, the research question has to be articulated quickly. Initially, the lack of specificity in some questions led to challenges in categorising responses for the second round of the Delphi, with some responses being very broad or vague (for example: income redistribution) and others being extremely specific (such as more effective limits on charging for school uniforms).

- Pre-specification is really important. Respondents sometimes mentioned the overwhelming nature of the survey’s second stage, citing the large number of items as a barrier to providing meaningful responses. It is therefore important to understand from the outset of the Delphi process what data will be categorised and how the results from the first phase will transfer to the second stage. This helps avoid bias in the approach and also helps formulate the questions.

- Be conscious of your sampling constraints. Given the nature of the task, there will sometimes be a low number of responses. And given the design of the survey, selection bias is likely to be present.

The feedback we received was instrumental in shaping our understanding of the Delphi process’s efficacy and limitations. It underscored the need for a delicate balance between comprehensive coverage of topics and the cognitive load on respondents.

We also learnt to categorise our issues, ensuring a clear distinction between causes, symptoms, and potential policy responses.

The Delphi method: a valuable policy tool

Despite its challenges, our experience with the Delphi method reaffirmed its value as a tool for policy analysis. It facilitated a structured yet flexible platform for gathering expert opinions, allowing us to quickly pinpoint areas of consensus and divergence. The method’s iterative nature, coupled with the anonymity of responses, also helped in reducing biases and promoting honest, uninhibited feedback.

Looking ahead, the Delphi method could hold significant promise as a versatile tool in the policymaker’s toolkit. Its application can be further refined to suit various policy domains, with modifications tailored to specific contexts and objectives.

Breaking the cycle: the outcomes model of public service?

Grace Duffy & Mila Lukic, Bridges Outcomes Partnerships

The threads of power and place run through everything we are exploring in UK 2040 Options. Understanding how power and place interact, and how they impact people and communities, is critical to understanding how we might make the UK a fairer place to live. This is part of a series of guest essays that explore how we might use new models of power and place to do just that.

Too many adults in the UK are stuck in a persistent cycle of unemployment, insecure housing and poor health. To break this invidious cycle, we need to think about public services – and invest in people’s skills – in a very different way.

Today, 4.3 million children in the UK live in poverty. In England alone more than 83,000 are looked after by the state, around 100,000 will leave school this year without qualifications and 20% are persistently absent from school. As a society we are facing intergenerational cycles of devastating outcomes cycles which can and must be broken to create a better society for the 2040 generation.

For the most part, the problem is not that the state is failing to reach the individuals behind these statistics. In fact, many of those in the most challenging circumstances have been through multiple public service interventions, at great cost and with good intentions, but without lasting success.

The problem is that we are not reaching the worst affected people early enough, and even when we do, the model for delivering services is fundamentally flawed.

A new paradigm for public services

In the UK, the traditional public services model is to standardise a particular process or intervention and deliver it in the same way, to anyone who needs it, as efficiently (and cheaply) as possible. This model focuses on immediate needs or problems to be fixed, and deals with them individually, in isolation – this is known as the ‘deficit model’.

This works very well for single issues with a ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution, such as mass vaccination or pension payments. However, it demonstrably fails to effectively address our society’s so-called ‘wicked problems’ – complex social problems without clear solutions, including multifaceted challenges such as family breakdown, long-term health conditions and homelessness.

This standardised deficit model has three key drawbacks. Firstly, by only focussing on ‘needs’ or ‘weaknesses’ (real or perceived) it can reinforce rather than break down the psychological barriers many people face when pursuing education and employment. Secondly, by focusing on isolated issues rather than trying to understand an individual’s situation more holistically, we often end up treating the symptoms rather than the underlying cause. And thirdly, it prohibits the personalisation needed to effectively address multifaceted challenges with complex interactions and instead takes a one-size-fits-all approach, treating everyone the same instead of treating them as individuals.

Fortunately, over the last decade, a new model of public services has started to emerge. This new paradigm recognises that what it takes to achieve positive outcomes is going to be different for everyone. It recognises that different places have different assets and priorities. It recognises that building on people’s strengths rather than focusing on weaknesses provides a better basis for sustained change. And it recognises that relationships are fundamental for thriving lives and communities.

At Bridges Outcomes Partnerships (BOP), we believe there are 12 essential ingredients when designing delivery to deal with these wicked problems.

Collaborative design

From programmes designed by a central department, often in isolation from other departments and implemented in a top-down way, to projects that:

- Bring community organisations together around a shared vision of success

- Co-create with real experts – frontline teams and participants themselves

- Join up with other local services via cross-government co-payment funds

- Operate as dynamic, actively managed partnerships by changing the nature of the contractual relationship between governments and delivery organisations.

Flexible delivery

From fixed-specification contracts that are delivered to rigid budgets for groups of people with identical needs to flexible, personalised services that:

- Tailor to peoples’ strengths by giving front-line teams the freedom to shape their services around individuals

- Invest properly in delivery teams by taking a more flexible approach to resourcing costs

- Embrace continuous improvement and allowing the service to be redesigned and ‘relaunched’ regularly

- Tackle systemic barriers to progress.

Clear accountability

From arms-length contracts with limited visibility on progress, success and key learnings to supportive partnerships which:

- Are transparent on progress by sharing regular updates against objective, clearly defined milestones

- Are accountable to those who access services

- Consider the longer-term impact of the service by finding light-touch ways to link into or compare with other government data

- Access and share learnings to benefit future services by investing in more sophisticated evaluations that tease out relative benefits of project features.

Since 2012, BOP has deployed these lessons through ‘outcomes partnerships’. These bring together multiple stakeholders to achieve meaningful change for people facing wicked problems, while helping create environments where delivery teams have more flexibility to personalise their delivery. By switching the focus to the desired goals rather than a specific delivery model, it allows for more personalised, localised programmes. The model also breaks down silos between systems to create more holistic – and therefore more effective – delivery of public services.

For example, in Kirklees, West Yorkshire, the local council recognised that its existing top-down, deficit-based model – using rigid service specifications focused on short-term needs – was consistently failing to achieve lasting change in people’s lives. So, together with the council, we created the Kirklees Better Outcomes Partnership (KBOP). Its strengths-based, outcomes-focused approach to tackling persistent homelessness, drawing on community assets, has been much more successful.

Of the 6,379 people KBOP supported since September 2019, 73% of people have been able to keep their accommodation while 49% have entered education or employment compared to 43% of people sustaining accommodation and only 15% entering education or employment in the initial year. These outcomes demonstrate ongoing innovation in delivery and are outcomes with long-term impact:

- KBOP has reduced the need for repeat support by over 70%

- has been able to support more than twice as many people than predicted

- at an average cost-per-participant which is 39% lower to the commissioner than under the previous service.

Moving to a holistic, strengths-based approach to delivery through outcomes partnerships has not only transformed lives, it has resulted in much better value for taxpayers’ money.

Breaking the cycle: skills and education

This emerging model has important implications for our approach to skills and education – an essential foundation of fulfilling, stable lives. Our work supporting adults who are homeless or at risk of homelessness demonstrates how this more personalised, strengths-based approach has helped practitioners approach skills in a different way and help people achieve sustained, positive changes in their lives.

Take the Greater Manchester Better Outcomes Partnership (GMBOP), a collaboration between mission-led organisations commissioned by Greater Manchester Combined Authority. This project supports young people at risk of homelessness. A lack of educational attainment was one of the biggest barriers to accessing stable employment and therefore housing. Many young people with highly transferable practical, creative and interpersonal skills are held back from jobs and apprenticeships because they don’t have a grade 4 GCSE in Maths or English.

By helping young people get qualified, GMBOP’s link workers have a huge impact, enabling them to access and sustain employment and accommodation. But first, they need to overcome the barriers that have stopped them in the past and lay the foundations for transformational change. This means taking a relational approach to improve resilience and confidence. And conceiving of skills in a wider sense to embrace essential soft skills such as communication, building relationships, setting goals and practical skills such as budgeting. Taking the time to develop foundational skills and focus on long-term outcomes helps these young people break their cycle of dependence on public services.

It follows then, that if we really want to tackle these problems we need to start early and prevent young people from getting trapped in these negative cycles in the first place.

That’s the key idea behind AllChild (formerly West London Zone), an outcomes-focused organisation that supports children and young people with an average of four risk factors across emotional, social and academic areas. None of these risk factors are, in isolation, bad enough to trigger statutory thresholds for children’s services. But taken together, they put the young person at high risk of negative outcomes, such as mental health challenges, being excluded from school, and/or falling into the ‘not in education, employment or training’ category.

AllChild’s two-year Impact Programme puts the child at the centre and personalises support around them, working with schools, early help, social care and local voluntary organisations to provide the tailored, holistic support they need. And it works. AllChild has supported more than 4,500 children across over 50 schools in West London. Three-quarters are no longer assessed as at risk in terms of their emotional and mental wellbeing, while two-thirds improved their grades.

A crucial factor in AllChild’s success is that it is deeply place-based. Extensive community co-design ensures interventions and services work in the local context, capitalising on local strengths. Indeed, building on its success in West London, this year AllChild has launched a new model in Wigan, Greater Manchester.

We need to change the system

These strengths-based, outcomes-focused programmes are hugely promising. But they remain the exception rather than the norm and there are systemic barriers to them realising their full potential. Most services designed to tackle ‘wicked’ problems are delivered with rigid service specifications that don’t allow for the personalisation possible under outcomes contracts – procurement processes and limited resources tend towards inflexibility, short-term budget cycles lead to short-term decisions and funding pressures result in prioritisation of crisis cases rather than prevention.

While this is understandable, it’s a false economy. Independent analysis (which has yet to be published) has found that outcomes partnerships such as AllChild deliver average total savings and wider economic benefits of £81,000 per child. This includes money saved by the state through the avoidance of negative outcomes, such as requiring child protection, and increased value from improved educational attainment and reduced exclusion. We must escape this ‘firefighting’ funding trap.

AllChild offers one potential solution. Partly because of its focus on place, it has been able to develop an innovative co-payment funding model. This brings together central and local government, local schools, local businesses and philanthropists to jointly pay for the positive outcomes the programme achieves, recognising that improving outcomes for children has benefits for the whole community. The model will soon be launched in Wigan – and can and should be replicated nationally.

Another crucial challenge is to target the right support, at the right time, to those most at risk of spiralling into negative outcomes.

In delivery, we see time and again the common factors trapping people in cycles of negative outcomes. And we see the enormous value of early intervention and prevention.

Where it’s been possible to securely link data sources, for example through Ways to Wellness, an asset-based social prescribing service, we have seen dramatic improvements in collective ability to understand what works and for whom leading to much improved outcomes for participants and cost savings to the NHS. With the advent of big data and AI, we have an opportunity to much more effectively target and tailor support for those who need it most.

The voluntary, community or social enterprise sector working on the frontline has a vital role to play in identifying those in need of help. Critically, the front line is the source of innovation and can also build the evidence base around how best to help people develop the skills they need to break negative cycles and improve their lives. We at Bridges Outcomes Partnerships would love to join forces with others who see the potential impact of truly holistic, place-based data and learning partnerships to get the right support to the right people at the right time. Given the likely state of the public finances over the next five years, improved targeting and investment in early intervention is clearly essential.

Solving these problems won’t be easy. Embracing this new approach to public services – more preventative, holistic and localised services and a strengths-based approach focused on improving individual outcomes – requires a change in mindset from commissioners and policy-makers. Breaking the cycle requires boldness and innovation. And if we get it right, the potential prize is huge.

Policy Live

Exploring policy solutions to some of the biggest challenges faced by the UK

Policy Live is a new event focused on exploring potential policy solutions to some of the biggest challenges faced by the UK. The one-day programme will convene influential leaders and emerging voices from across governments, the civil service, NGOs and the private sector.

Join us on Thursday 12 September to hear optimistic solutions to some of the UK’s biggest policy challenges, forge connections with other policymakers and influencers, and discuss and experience innovative policymaking ideas.

- Hear from insightful speakers from across the political spectrum tackling era-defining issues.

- Engage with keynote speakers on critical topics like the economy, public health, education, the environment, and technology.

- Take part in interactive sessions and hands-on workshops.

- Connect with fellow policy professionals, expand your network and gain new perspectives.

- Enjoy all-day refreshments and a workspace at our central London venue, just a short walk from Westminster

Visit the event website for more information, to see our list of confirmed speakers and to register for your complimentary place.

Event information

- 12 Sep 2024 09:30 – 18:30

- etc Venues, County Hall, London

- Free to attend