Capacity crunch: the biggest challenges facing the next government

Sam Freedman is a political journalist, author and former policy adviser at the Department of Education. He has conducted an analysis of the UK 2040 Options reports on economic growth, health, education, tax and public finances, wealth and income inequality, and power and place. In this report, he draws out the cross-cutting themes that span the UK government’s most pressing challenges.

The UK is in a bad place – stuck in a loop of low growth and productivity, with underfunded and inefficient public services, record low levels of trust in politics and a general sense of frustration from across the political spectrum, regardless of ideology.

But there is nothing stopping us from turning it around by 2040. That’s the timeframe that the UK 2040 Options project is looking to: it has commissioned analysis in topic areas that will be critical to deciding what our future will look like.

There’s a long list of things we could do, it’s just that the nature of our political system makes it so hard to do them. Only by tackling head on these broader cross-cutting political challenges can politicians steer us through our current problems to a more optimistic future. And they need to get on with it, because the list of demands on the state is only going to grow.

- By 2040, there will be much higher healthcare, social care and pensions costs due to an ageing population. Chronic health conditions are projected to affect a substantially greater number of people.

- Decades of underinvestment in capital and infrastructure risk driving future costs in acute crisis management even higher. We can already see this playing out in the NHS and the criminal justice system, among other examples.

- There is a growing number of external risks, including worsening global security following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, growing tensions in the Middle East, and concerns about China. The effects of climate change will increase and we have learned the hard way the need to be prepared for pandemics.

- The rise of the ‘regulatory state’ has meant a big, and largely undiscussed and unplanned, increase in regulatory costs for public and private institutions. There is ongoing pressure for further regulation across multiple sectors – often with good cause.

The UK isn’t unique in this regard. Countries across the world are facing similar challenges, but there are elements of the UK’s political set-up that make them particularly difficult for us to deal with.

- The UK is uniquely centralised. This puts huge operational pressure on the centre, while leaving local government weak and unable to raise its own funds. There are major regional disparities in wealth and productivity that are, in part, driven by this lack of power at regional or local level.

- The UK has a constitutionally extremely powerful executive combined with weak central institutions that struggle to use this power effectively. Government ministers rarely last more than a year or two. Attempts to reform the civil service have been half-hearted at best and it has been left largely as originally designed.

- The Treasury is unusually powerful for a finance ministry and essentially holds veto power over everything that happens in government, meaning it sets the de facto strategy.

- The UK has a highly centralised political culture that is caught up in a super-fast media cycle. This leads to a focus on communications at the expense of policy, which paradoxically creates a loss of trust with the public.

Managing demand for services will require the state to spend more upfront. Some of this can be achieved through better taxation but mostly it requires growth through improved productivity. It will also need more efficient public services through greater investment in infrastructure, technology, and prevention. This is well known and has been for a long time. There isn’t a shortage of ideas about how to do these things, but our structural constraints keep getting in the way. To tackle them effectively, politicians need to confront the ‘meta’ cross-cutting challenges of the way our state works.

The UK needs:

- more effective central institutions that are able to support ministers in decision-making, rather than the haphazard collection of structures that have evolved over centuries

- more capacity at regional and local level, with more operational functions devolved to them and more ability to decide strategy for regional economies and services

- more effective engagement around democratic trade-offs, through greater transparency and accountability, as well as exploring new ways to assess the public-preferred routes through difficult trade-offs

- a clearer framework for regulation, risk and prevention, rather than the entirely arbitrary and poorly evaluated and costed approach we take at the moment.

There are many different approaches politicians could take to create a new political settlement. But we will only get to 2040 in good shape if we have one. What we have now isn’t up to meeting the challenges we face.

Download the full PDF report

How the citizen incubator model could reimagine the way we tackle our most pressing social problems

James Green, founder and CEO of Public Life

The threads of power and place run through everything we are exploring in UK 2040 Options. Understanding how power and place interact, and how they impact people and communities, is critical to understanding how we might make the UK a fairer place to live. This is the first in a series of essays that will explore ideas about how we might use power and place to do just that.

What will life be like in the UK when today’s children reach adulthood? The question Nesta has posed through UK 2040 Options is the same one that is being discussed with growing pessimism at school gates and dinner tables across the country. It is no surprise: hope is in short supply and trust is at a record low.

However, there is reason for optimism. As trust in traditional institutions has fallen into sharp decline, new models of public-led activism, innovation and ownership are on the rise, catalysed by technology. Yet, despite this, the way we design solutions to our biggest public problems has barely changed for centuries, with decisions made by a small number of people in an even smaller number of institutions. This creates an opportunity. If we can get this right, we can inspire a new generation of citizens to lead the way in helping tackle some of our most pressing social issues. If we can’t, there is a risk that declining trust in institutions turns into a loss of the public consent on which their power resides.

The citizen incubator model

For the last twenty years, I have worked in and around public life. I have seen it from the inside, heading up the offices of MPs, and have influenced it from the outside, leading national lobbying teams and creating UK-wide campaigns.

These experiences have led me to conclude that there is a fundamental flaw at the heart of UK public life – it doesn’t actually involve the public. From Whitehall to town halls, the people creating solutions to our biggest social issues are almost never the ones facing them on the ground. This has left the public on the sidelines, disempowered by a system that often sees them as a problem to be solved rather than an asset to be unlocked.

The evidence is clear that public trust and citizen engagement are mutually reinforcing. Yet, as the Institute for Government point out in their in-depth review of the UK constitution, there are “limited opportunities for citizens to shape the decisions that affect their lives in a meaningful sense.” This has contributed to growing scepticism amongst the public in the institutions that represent them. Recent YouGov polling found that 56% of people believe parliament does a bad job of representing their interests, with only 11% saying it did a good or fairly good job. Hansard Society research reinforces this, finding that 50% believe the main parties don’t care about “people like me.”

Creating a new approach that puts citizens in the driving seat has been my obsessive focus over the last seven years. I wanted to rebuild trust and agency, so designed the ‘citizen incubator’ model to both support those facing social issues to invent the solutions they need, and inspire citizens to recognise their own power to lead change. That’s why the approach is not just about ideas. Equally as important are the opportunities thousands get to play their part as active citizens and their impact on the hundreds of thousands reached through their work. In this way the model is as much about incubating citizenship as it is new solutions.

I have designed and delivered multiple programmes using the model, with thousands of citizens and hundreds of organisations involved, and a range of new community-led businesses are now in the world as a result. An independent university evaluation of the last programme using the model found that in its first year alone, it generated a social return of £6.26 for every £1 invested.

The citizen incubator model has three key elements:

- Citizen facilitation. A unique approach that identifies and recruits active citizens facing social issues as citizen entrepreneurs and pays them a living wage.

- Community innovation. A five-phase process that supports citizens to spend a year inventing impactful solutions with thousands locally.

- Funder collaboration. A model that involves funder organisations throughout, with them ready to invest in credible citizen solutions.

This is the story of the most recent citizen incubator programme.

A mission-led approach

Eastlight Community Homes wanted to be bold and invest in a different way in its North Essex communities. As the biggest community-led housing organisation in the country, its board was passionate about putting power firmly in the hands of local people. The citizen incubator model gave them a chance to support them in a radical new way.

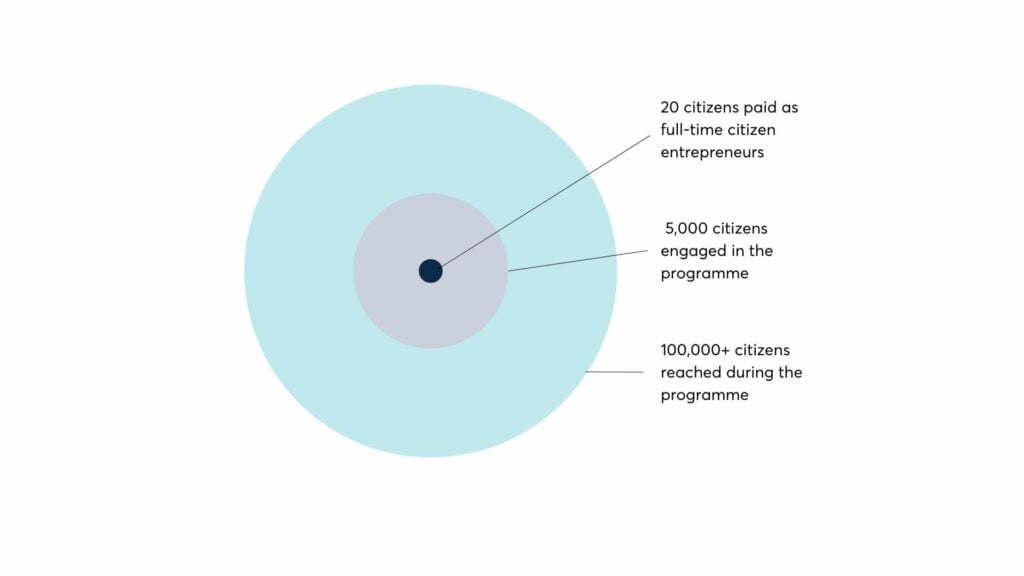

The programme I designed involved recruiting 20 Essex residents and paying them a full-time living wage salary to dedicate a year to going from a blank sheet of paper to inventing new solutions with thousands locally. Based in teams in the Essex towns in which they lived, these citizen entrepreneurs took on four community missions. These focussed on the social issues facing them and their communities, informed by polling we had commissioned locally. We wanted to understand how the model worked in different settings so focussed on a range of geographies, from Halstead, a town with a population of 12,000, to Colchester, a city with a population of 130,000.

The citizen entrepreneurs went through a 12 month innovation process. This involved leading ethnographic research to get under the skin of their problem, running workshops across their communities to generate ideas, designing experiments to test the best of those with local people, and finally delivering their solutions on the ground with a six-week pilot. My team provided the support they needed, but they took every decision. The big question was – through this mission-led approach, could citizens with no experience of social innovation invent impactful new solutions to the issues facing them?

To answer that question we commissioned the University of Essex to independently evaluate the programme. They found the model created impactful citizen solutions to complex social problems, strengthened communities by building trust and engagement, and delivered life-changing experiences for the citizen entrepreneurs.

Impactful citizen solutions

The teams created genuinely impactful solutions to the problems important to them. Each was piloted on the programme with measurable impact. The university calculated a collective social return on these pilots of £668,000. The citizen entrepreneurs went on to use this evidence for their funding proposals, with every one going on to win funding and spin out as its own community-led organisation. Crucially, every aspect of the solutions creation, development and implementation were informed by direct life experience of the social issues they were working on.

A great example was Karen and her Colchester team (which included her daughter Jessica), who had taken on the community mission of the cost of living. Their insight was that those who have the least money are often the best budgeters. And they knew that because that had been them. That insight became Trusted, an innovative peer-to-peer money confidence programme, the first of its kind in the UK. The team piloted Trusted on the programme and its impact blew them away. In the space of just six weeks, the ten pilot participants collectively saved nearly £45,000. Trusted went on to secure funding and become its own community-led organisation with Karen and Jessica at the helm. They have run a number of programmes since, all with similar results, and are busily working to scale the model.

Stronger communities

The University found that “the programme created genuine trust and engagement and fostered community in multiple directions and levels.” Over 5,000 local people engaged with the citizen entrepreneurs over the 12 month period, half of them in person. This was a collective endeavour with the community getting involved because it was their friends and neighbours taking the lead and working on issues that were affecting their lives too.

The reach of the programme was also significant. We estimate their work reached over 100,000 people locally. This was important to us as it demonstrated to local people, with tangible relevant examples from their communities, the power they had as active citizens.

The community incubator model has reached over 100,000 people in North Essex

Life-changing experiences

By offering a full-time living wage salary and recruiting without asking for a single CV, we managed to reach people who would never have previously seen themselves doing this sort of work. This included people in low-paid precarious work as well as those who had been out of work for years. We had 100% retention of participants, 67% of the paid community participants went on to better jobs in the months immediately following the programme (defined as either better-paid work or leading the solutions they had invented), and there was a 60% average increase in networks for participants as a result of the programme.

We measured a range of self-reported outcomes at the beginning and end of the programme covering dimensions including mental health and wellbeing, enhanced employability, confidence, skills, and social isolation. Questions were based on the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scales, a widely used methodology for measuring wellbeing that has been validated in a range of settings. As a cohort, there was a positive and statistically significant shift across almost all self-reported outcomes, demonstrating the direct impact of the programme on different aspects of the participants’ lives.

Taking into account all of these impacts the university calculated that in its first year alone the programme generated a social return of £7.5 million. And this “conservative figure” only takes into account its impact during the year it was active. It does not include the programme’s longer-term impact on the participants, communities or of the solutions they created. “This means”, the university concluded, “that for every future year the social impact of the programme is likely to increase considerably.”

A new vision of public life

Imagine if citizens in communities up and down the UK were supported in this way to invent new solutions to the social issues facing them. Not only would we have a wide range of new community-led solutions to some of our most intractable social problems, we would also have hundreds of thousands of citizens involved in the process of creating change. The scale of impact could be transformational.

At the local level, new social businesses would be making a tangible difference at the grassroots, created by citizens for citizens. And at a national level, a different relationship would begin to emerge between citizens and the institutions that shape their lives, rooted in meaningful partnership. With hundreds of thousands of citizens involved and millions reached, public life would feel very different. All of us would gain a deeper understanding of how problems are experienced on the ground, benefit from the insights and solutions that can only come from life experience, and see citizen-led change catalysed in ways we would never have predicted. This would be a different type of public life – one boldly led by the public.

The most wealthy need to pay more tax: here’s what the UK can learn from the rest of the world

John Craven, Executive Officer at System 2

UK 2040 Options recently analysed the current state of wealth and income inequality in the UK. The experts they engaged with were clear that taxation is a key factor that is ripe for reform.

In the twelve years I spent working in financial markets, wealth management and tax consulting all over the world, I gained valuable insight into how businesses and rich individuals respond to the incentives that tax systems around the world offer them. More recently, as a teacher, a charity CEO and the Director of the Social Mobility Commission, I’ve seen firsthand the impact that high levels of inequality have on society.

This blog draws on these experiences and explores some realistic options for policymakers to reduce inequality, which have been tried and tested in other countries.

It’s not inevitable: a reflection on the international context

The IFS sets out how poor tax design in the UK is a major challenge. Certainly, if we were able to redesign the tax system from scratch, it could reduce inequality and damaging distortions, while improving productivity and economic growth. But in reality, we know that political constraints mean that reform is often slow and incremental, and it can take time for new ideas to gain acceptance.

Whenever a new tax is proposed, or the reform of an existing one is recommended, those who are adversely affected lobby hard to maintain the status quo. Practical proposals, sensible reforms or attempts at simplification (such as the “Pasty Tax”) are often dismissed as impossible to implement, unfair when considered in isolation, or likely to result in damage to the economy. The result is tax inertia. Instead of optimising policy to minimise distortions, improve incentives and raise productivity, policymakers make fewer changes, instead using devices such as fiscal drag to increase revenue.

The resulting set of income and wealth taxes in each country throws up some surprising differences. What some consider to be radical policies in the UK are uncontroversial elsewhere. For example, unlike the UK, Australia (where I am currently based) has no inheritance tax and the state pension is means-tested.

How ultra-high-net-worth individuals avoid tax

As a director at a global wealth management firm, that included a Swiss private bank, I oversaw complex investments for wealthy clients, spending much of my time in cities such as Dubai, Geneva, London, Monaco and Paris. I often met ultra high-net-worth clients, with at least $25-50 million in net assets. I listened as advisers explained how they could avoid tax.

Most sought to minimise their tax liabilities where it was clearly legal and involved limited disruption to their lifestyle. If it was legally or reputationally risky, or hard – such as requiring a move abroad – they were more likely to decide to stay and pay the sticker price taxes. Some were happy paying local taxes on income and capital “in full” since the country had enabled them to generate that wealth. A few, particularly those with fewer ties to the country, sought to pay as little as possible, even when that involved taking risks or moving to a tax haven.

One British man I met in Monaco had sold his UK business and was there for five years to avoid paying millions of pounds of UK taxes on his gain. He could still visit the UK but only for a limited number of days each year. When I first went to his apartment, he would stand on his balcony overlooking the harbour, and tell me how lucky he was. The third time we met he told me how much he missed his family and couldn’t wait until he could move back to spend more time with his grandchildren. I’m sure that if the rule had been ten years not five, or he was allowed back in the UK for even fewer days, he would never have left England and paid his taxes there. The set of choices we gave him incentivised him to avoid paying tax here.

To the extent international law permits, we can start by changing that.

But we must go much further than simply tightening up rules on the number of days that small numbers of wealthy UK citizens who become non-resident can spend in the UK without triggering tax implications. Understanding how other countries have introduced similar taxes can help us overcome the inevitable resistance that the threat of a new tax brings.

Seven practical ideas for policymakers to reduce inequality

1) Increase the Stamp Duty Land Tax surcharge for non-UK-residents purchasing UK residential property from 2% to 15%

International ownership of housing can increase inequality. It can reduce the supply of housing available for locals, increase rents and house prices and make it harder for young British people to own their own home. Hamptons estimated that in 2023, 24% of homes sold in Greater London went to international buyers, rising to 45% of those in prime Central London.

Other developed countries have taken much bigger steps than the UK to deter foreign ownership, or at least to raise greater taxes from it. At one extreme, Canada has banned foreign purchasers altogether, until at least 2027. The situation is similar in New Zealand, with some exceptions for temporary ownership of newly built housing. To buy in Switzerland, foreigners need a permit, only 1,500 of which are issued each year through cantons. Singapore recently doubled the additional stamp duty paid by foreigners buying residential property to as much as 60%. In Australia, foreign buyers will soon be hit by extra fees and taxes totalling 14%-17%.

In comparison, the UK charges foreign buyers a mere 2% supplement, with few restrictions on owning property in the UK. Increasing the rate to 15% could deter overseas buyers, freeing up property for local buyers, while bringing in revenue from the most determined. Halving the rate for new-build flats could prevent the risk of this policy reducing the housing supply.

2) Increase the higher rates of Stamp Duty Land Tax for those purchasing additional existing homes from 3% to 6%

It is not just overseas buyers that compete for property with first-time buyers. Local residents also acquire second homes and investment properties. Singapore citizens and permanent residents buying their second or subsequent properties pay a 20%-35% supplement. In comparison, the UK charges those buying additional properties only 3% more. Doubling this to 6% for existing properties would bring in much-needed revenue. Exempting new-build flats could prevent the risk that this could reduce supply.

3) Create a new Annual Property Tax on market-based hypothetical rental income, charged to owners of all homes, except UK resident owner-occupiers

One way to ensure properties are more likely to be rented is to tax vacant properties as though they are let. Many countries take this approach. Property owners in Switzerland must pay income tax on a property’s perceived rental value, deducting mortgage interest payments and maintenance costs, in addition to taxes on the value of property and wealth. Singapore applies a tax on property ownership, whether the property is occupied by the owner, rented out or left vacant. A tax rate of 12%-36% for non-owner-occupiers is charged on the estimated gross rent of the property with owner-occupiers charged less. In the UK, council tax is the closest to a property tax, with properties put into one of eight bands based on values in 1991. The IFS recently set out how council tax is highly regressive with respect to property values and leads to increasingly arbitrary tax bills.

While some councils are doubling the council tax on second homes and empty dwellings, a more consistent approach nationally would be to create a new Annual Property Tax on a market-based hypothetical rental income. This could be charged to owners of all homes at marginal income tax rates, except UK resident owner-occupiers – so would be paid by owners of second homes, rental properties and vacant properties. Those that are rented out would pay tax on the actual rental income achieved if higher and could deduct relevant costs. If not rented for at least six months of the year, no deductions would be allowed, and a flat 45% tax rate on the hypothetical value would be applied.

4) Prevent individuals with assets in ISAs above £100,000 at the beginning of a tax year from investing in a new ISA that year

Most developed countries offer tax incentives to save for retirement, but very few are as generous as the UK in offering easy access savings accounts sheltered from tax. ISAs allow UK taxpayers to invest £20,000 each year without paying any income or capital gains tax on profits. Those with lower incomes and wealth typically have lower total savings and do not benefit from this significant tax break.

At the same time, the more affluent have accumulated significant savings, returns from which are permanently sheltered from tax. Over 4,000 people have ISA savings that exceed £1 million. It would be considered unconventional and unfair to make ISA savings above a given threshold taxable again. Preventing people with ISA savings above £100,000 at the beginning of the tax year from opening a new ISA that year would mean they would need to pay income and capital gains tax on investment returns from the savings they are no longer able to put into the ISA.

5) Create a new Retirement Savings Allowance tax charge on pension assets above £500,000 at age 70

A common definition of a pension is that it provides those who are retired with a regular income, not that it is a savings vehicle or investment account. Indeed, until it was abolished in 2011, pensioners had to use their (defined contribution) pension savings to buy an annuity, which provided a fixed income for life. Yet, for many wealthy investors whose pension savings exceed the £1,073,100 Lifetime Allowance, their pension is not used to generate an income on retirement but is part of their inheritance tax planning strategy and used as a store of wealth. As such, the upcoming abolition of the Lifetime Allowance is an unnecessary reduction in tax for some of the most wealthy in the country.

The Lifetime Allowance was introduced in 2006, capping the amount of pension savings that can be built up without incurring a tax charge, typically of 25% (it was reduced to 0% this tax year). The limit was repeatedly decreased in real terms but is now due to be abolished altogether in April 2024. The changes reduce the potential tax liability of those with pension savings exceeding the limit when they retire and hence increase inequality. Meanwhile, Australia is raising pension taxes, not abolishing them, introducing a new 30% tax on pension balances above AUD$3 million (roughly equal to £1.56 million) from July 2025.

There would be challenges in reinstating the Lifetime Allowance, so instead, a new Retirement Savings Allowance (RSA) could be introduced set at £500,000, but only applied on savings, not annuities (providing a fixed income) that have been purchased or defined benefit pensions. The vast majority of people are unaffected, and those who use their pensions as intended — to generate an income rather than to store wealth or avoid inheritance tax – don’t lose out. To maximise the impact, while giving people time to buy an annuity at a time that suits them, this RSA test could be applied to all with at least a year’s notice at age 70 or later.

With pensions, there is always a lot of detail to work through, so I don’t pretend this comes close to covering it!

6) Create a new 1% wealth tax charged on net assets above £2 million

In 2020, the Wealth Tax Commission published a report setting out how a one-off wealth tax could be designed as an exceptional response to the fiscal costs of the Covid-19 pandemic. It set out how a 1% tax on individual assets above £2 million could raise £80 billion over five years. It added that a more permanent “annual wealth tax would only be justified in addition to these reforms if the aim was specifically to reduce inequality by redistributing wealth”.

There are additional challenges with an annual wealth tax, including measuring hard-to-value assets, and fears that it would drive away mobile wealthy individuals, damaging the economy. Countries such as Switzerland have shown these can be overcome. All Swiss cantons impose a wealth tax on net assets, even for low levels of wealth. For example, for net assets above 82,200 francs, Geneva has a rate of 0.149%, with marginal rates rising as wealth increases, and exceeding 1% in some cantons. It generates as much as 3.8% of total taxes in Switzerland.

7) Create a new British Citizen Tax, mirroring the wealth tax, payable by all wealthy British citizens living overseas

One issue with a Wealth Tax is it could incentivise wealthy British citizens to move overseas to avoid it, which would reduce the tax raised. In the US, citizens are fully subject to US tax on their worldwide income and gains, no matter where they live, unless they renounce citizenship. Issues such as the administrative burden it creates for those of more modest means, and double taxation of income, means that some specialists say it would be unwise for the UK to replicate it. Instead of taxing income and capital gains, a wealth tax payable by those British citizens living overseas with net assets above £2 million could overcome many of the problems, if it could be designed in compliance with international rules. Those with assets below that would need to make a simple annual declaration listing valuable assets and provide copies of local tax returns to HMRC. Wealthy UK citizens living permanently abroad would need to renounce citizenship if they wanted to avoid the tax.

Some of the revenue from these new taxes could be used to reduce other taxes, both to reduce inequality further and to improve the efficiency of the system. Personal allowances could be increased to improve incentives to work and raise post-tax incomes of lower earners. Incentives for higher earners could be improved by reversing the removal of child benefits and the personal allowance from higher earners that currently creates very high marginal tax rates of 62% or more. Finally, a permanent halving of all basic levels of stamp duty would increase transactions, improving the geographic mobility of workers and removing the incentive to move as infrequently as possible.

Mythbusting: reform is not impossible

I acknowledge that some of the above is necessarily a simplification of a complex system. I don’t underestimate the challenge involved in creating an environment that allows for major change.

But I hope that at least by showing how other countries use similar taxes, it destroys the myth that these taxes are impossible to implement in the UK. And that this brings forward the day we might move to a fairer tax system that reduces inequality.

John Craven is Executive Officer at System 2, a charity set up by The Behavioural Insights Team and Nesta. It aims to solve complex social problems by bringing together behavioural science, systems thinking and insights from deep collaboration with those with lived experience, to co-design, test and scale practical solutions.

He is also an Honorary Fellow in Educational Equity at the University of Birmingham. Formerly he was a Director of Global Wealth Management, Bank of America, and was the former Director of the Social Mobility Commission in the UK.

How local authorities are using data to solve problems like homelessness

With enough investment and ambition, local councils can use data to help solve some of society’s most intractable problems.

By Rachel Carter and Lucy Makinson

The devolution agenda is likely here to stay. Local councils are closer to their communities and are often better-placed than central government to grapple with their most complex challenges.

To better understand the data challenges faced by local government, and to surface the opportunities that exist through devolution, Nesta’s UK 2040 Options hosted a panel event in late November 2023. Chaired by Nesta’s James Plunkett, panel members were Stephen Aldridge (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities), Cate McLaurin (Public Digital), Gavin Freeguard (freelance consultant and host of the Data Bites event series), Wajid Shafiq (Xantura), and Natalia Merritt (Maidstone Borough Council).

This is what we learnt.

Preventing homelessness through harnessing the power of locally held data

Data is both a strength and a weakness when it comes to local delivery. Everything, from the provision of social care for vulnerable children to collection of council tax, produces a huge quantity of data. This data could have huge benefits for councils; helping them better understand their citizens’ needs and behaviours, targeting services more effectively, stopping what isn’t working, and allocating resources to where they have the biggest impact. But in practice, it can be challenging for councils to use this data effectively. It can sit in siloes, and local authorities can lack the capability, time, or investment to draw out what the data means and to utilise it as effectively as possible to improve public service outcomes.

But it quickly became clear that effective use of data by a local council can be transformative. Natalia Merritt spoke about Maidstone Borough Council’s partnership with Xantura to create Oneview: a multi-agency identification system that enables Maidstone to understand which households may be imminently at risk of homelessness. It uses data and predictive analytics to understand the risk factors that contribute to homelessness and alerts the council to households that are at risk, who can then receive targeted early intervention and support. An initial assessment of the programme found that it is accurate in identifying imminent homelessness in 84% of cases.

Often, councils only become aware of an issue when people tell them they have become homeless, which is too late for any preventative intervention and increases reliance on expensive temporary accommodation. Maidstone can only prevent homelessness for a third of the people who walk through their door. However, the preventative approach facilitated by Oneview – of targeted early intervention and support – has already paid dividends. Of the first cohort flagged through the system, only 2% became homeless after early intervention action was taken. This preventive approach has resulted in huge cost and time savings for the council.

Laying the foundations for policy success: it’s about more than just data

Maidstone was able to execute its vision of preventing homelessness in the borough through two key enabling factors. Firstly, it had senior leadership with an ambitious but clear vision of what it wanted to achieve, who gave permission and encouragement to tackle this problem head on. Secondly, it had an initial investment that enabled it to establish Oneview.

Our panel members highlighted the factors they saw as critical to creating an enabling environment for local authorities to use data effectively.

- Focus on the use cases, not the data. As one expert put it, “if you want to have a conversation about data, don’t talk about the data”. Data infrastructure and capabilities might be important, but they are not the end goal. Showing people what they can do, and the outcomes they can achieve, through the use of data is far more effective for creating buy-in. This is particularly important for busy frontline staff.

- Senior leadership needs to be on board. We heard that when senior leaders ask the right questions – like in the Maidstone example – they can create a permission space that enhances and accelerates innovation.

- Starting small can pay off in the long run. Getting a small grant, kicking off a programme and working with a first cohort can enable you to test and see if a programme will work. That pilot can then be used to test, evaluate and adapt.

- It’s about more than the data itself. All experts agreed that impact doesn’t just come about with better data, or even improved data capability at the local level. They called for a continued focus on robust policy evaluation, evidence and insight, including tracking impact over time, to deeply understand what works and reallocate resources at pace to what works best.

Large structural challenges can hamper councils’ ability to use data

Panel members were conscious that local councils are currently operating in a challenging context. And while data use can drive some very visible and positive change, the barriers to reaching this for much of local government were repeatedly raised. To harness the potentials at the local level, any next government will need to grapple with several challenges.

- The lack of investment in councils. This is preventing councils’ ability to fix legacy systems – many of which make it very difficult to bring data together around a household, or a citizen.

- The variation in performance between service providers. Even allowing for differences in local costs and the characteristics of the population served, this remains a problem. Reducing this variation by raising the performance of those lagging behind could have valuable impacts on outcomes achieved. And, our experts told us, the newly established Office for Local Government could have an important role in supporting this.

- A monopoly on services. Some panel members spoke about the need for reform in the market for local authority systems and processes. Currently dominated by three of four big suppliers, it is often difficult to get data in or out of these systems, hindering the ability to effectively use the data.

- Barriers exist that prevent data sharing and enhance legal concerns. A lack of legal gateways for accessing and linking administrative data across central and local government, and even within local government itself, was repeatedly raised as a challenge. There is work underway in this space. ONS for example is developing an integrated data service, which – if it works – could overcome the need to put in place legal gateways. At the same time, legislation has often not caught up with technological advancement in this area and is often out of date.

- A lack of “patient capital”. Most interventions are not going to turn problems around quickly – we know that many interventions take time to bed in and to come up with findings, whether they are positive or negative. “Patient capital”, or long-term investment, means that public services can invest in working out what’s working and what’s not, over multiple partners and through different terms.

A way forward?

Maidstone showed us that with investment and ambition, local councils can use data to build the evidence base and draw out invaluable insight, forging a path to solve some of society’s most intractable problems.

But while effective use of data can help, it is only as good as the ability or capacity to do something useful with it out in the real world. And while many local authorities are well placed to gather and use the data they hold to solve problems, there remain significant hurdles to them doing so. This is the case whether it’s about solving homelessness in Maidstone, grappling with methodological challenges to get to grips with what works, or using data to better target services to improve the first years of a child’s life.

At Nesta, our aim is to innovate for social good. And in doing so, we want to give local decision-makers and policymakers the right tools to drive positive change. Nesta’s fairer start mission is working at the local level to explore methods to eliminate the school readiness gap. As part of this, it is hosting an event to help local authorities come together and share ideas on how data can improve services for children and families. Visit the event page to learn more.

A new ‘Neighbourhoods Unit’ could shift the dial for UK inequality

Matt Leach, Local Trust

Global challenges will provide a backdrop to many of the big decisions that will face us through the 2020s and 2030s – most notably regional conflict, growing climate instability and faltering economic growth. But the UK faces equally pressing questions at a local level.

Quality of life, design and delivery of public services, the shape and limits of the state and how all of this links to issues of identity and connection are critical to how we experience our lives, collectively and individually.

Brought together under the themes of “power and place”, they were the subject of a fascinating workshop hosted by UK 2040 Options and chaired by Demos’ director Polly Curtis, and a subsequent report.

With politics increasingly polarised and both nation and the wider global community facing an endless succession of intractable challenges, attempts to build consensus on the key issues facing us and cross political lines in a search for solutions are both rare and valuable. The UK 2040 Options project falls into the category of initiatives that are both incredibly timely and hugely important.

Rebuilding communities

Seeking to explore two important areas of policy thinking – how we are governed and people’s experiences of life at a neighbourhood level – the workshop examined the case for devolution of power and its limits. It also looked at the growing evidence base highlighting the need for new policy initiatives focused on rebuilding community institutions at a hyperlocal level.

As was noted at the workshop, one of the biggest challenges in developing policy in this space is the extent to which debates around what is often labelled “community power” conflate a number of very different strands of thinking.

On the one hand, there is a very developed debate around issues of devolution, seeking to shake out the best place for state-focused decision-making to sit. This tends to focus on tussles between Whitehall and local government, with the primary argument often being that this would establish conditions for better (or more balanced) economic growth. Alongside this runs a debate over the form of local government, and in particular, the benefits of mayors and combined authorities as both more effective and more accountable models of local governance.

A separate debate focuses on the extent to which local authorities should involve local people in service design and decision-making. Advocates either claim this as a good in itself, or point to ways in which this can improve delivery. Much of this builds on the excellent work of organisations like New Local and its Community Paradigm model.

A final strand of thinking has, until recently, been less well-represented in national policy debates, but is arguably more important to the everyday experiences of people. This is the need to address challenges and inequality at a neighbourhood level, highlighting that these are often as profound as regional differences in outcome.

Neighbourhood-level inequality

Drawing on extensive evidence from evaluations of the hugely successful New Deal for Communities programme, and more recent initiatives such as Local Trust’s own Big Local programme, this line of thinking focuses on the need to rebuild and strengthen local community organisations and institutions as a means of driving better outcomes.

One of the primary drivers of outcomes at a local level, even after accounting for relative levels of deprivation, is the strength of neighbourhood-level social fabric, as we have seen in reports such as Demos’ Preventative State. And that – often – the challenges faced by the state are driven by the need to address the social costs arising from the breakdown of these social structures.

The rise of the ‘social communitarians’?

To help make sense of all of this at the workshop, Demos proposed the existence of three broad policy “tribes” seeking to define the policy landscape in this space. The federalists, focused almost exclusively on issues of devolution of power; the mayoralists, largely focused on the transfer of power to individually accountable local leaders at a city level; and the communitarians, largely focused on building/rebuilding grassroots-level civic institutions and perhaps more agnostic about constitutional reform.

This classification of different approaches feels helpful, not least as a means of ensuring that crucial parts of the policy jigsaw are not lost as a result of shared terminology inadvertently concealing very different policy priorities. But there may be value in seeking to distinguish between two distinct strands of thinking within the communitarian camp.

There are those who see community power within the context of further devolution of power from the state – we can call these ‘democratic communitarians’, who in many ways simply reflect a logical extension of the agendas of federalists and mayoralists. There are also the ‘social communitarians’, who would argue that equal priority should be given to building or rebuilding social and civic institutions at a local level as a good in itself.

While the federalist, mayoralist and democratic communitarian camps have been well-represented in recent policy debates, we have seen little focus on neighbourhood-level policy in recent years. Since the Social Exclusion Unit’s report on a national strategy for neighbourhood renewal 25 years ago, we have had little in the way of new initiatives or engagement with neighbourhood-level, community-focused policy interventions since.

With an election likely in 2024, there seems little time left for either party to initiate new debates or come forward with major new initiatives focused on delivering neighbourhood-level change. But the establishment, post-election, of a new Neighbourhoods Unit, which could build on the example of the Social Exclusion Unit and focus on collating evidence and developing policy on rebuilding the social fabric of local communities, would be a major step forward in addressing a significant gap in our policy landscape. Is it time for a return of the social communitarians?